Above: From the east side of Washoe Lake, the view of Slide Mountain and Mount Rose on January 7, 2018, showed the effects of the ongoing snow drought. Warm wet and dry periods in November and a dry period in December created snow drought conditions throughout the region. Credit Benjamin Hatchett, DRI.

Reno, NV (Wednesday, January 17, 2018): The Lake Tahoe Basin and northern Sierra Nevada are currently experiencing a condition known as snow drought, according to new research and data from scientists at the Desert Research Institute (DRI). Snow droughts, or periods of below-normal snowpack, occur when abnormally warm storms or abnormally dry climate conditions prevent mountain snowpack from accumulating.

“As of early January, the snowpack in the Lake Tahoe Basin was only 28 percent of normal,” said Benjamin Hatchett, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher with DRI’s Division of Atmospheric Sciences. “We experienced warm wet and dry periods in November and a dry period in December that has created snow drought conditions throughout the region, followed by warm, rainy weather so far in January that has caused snowpack levels to decline further, especially at low elevation sites.”

Snow droughts have become increasingly common in the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains in recent years, as warming temperatures push snow lines higher up mountainsides and cause more precipitation to fall as rain.

Hatchett, an avid backcountry skier, began to notice the trend several years ago and recently published research outlining an approximately 1,200-foot rise in the winter snow levels over the last ten years across the northern Sierra Nevada.

Looking deeper into the rising snow levels and a general continued lack of snow in their local region, Hatchett and fellow DRI climate researcher Daniel McEvoy, Ph.D., an assistant research professor of climatology and regional climatologist at DRI’s Western Regional Climate Center (WRCC), sought to expand upon the little that is currently known about snow droughts and their impacts to local watersheds and economies.

In a new study recently published in the journal Earth Interactions, Hatchett and McEvoy explored the root causes of snow droughts in the northern Sierra Nevada, and investigate how snow droughts evolve throughout a winter season. To do this, they used hourly, daily and monthly data to analyze the progression of eight historic snow droughts that occurred in the northern Sierra Nevada between 1951 and 2017.

“We were interested in looking at the different pathways that can lead to a snow drought, and the different implications that each pathway has for mountain systems,” McEvoy explained.

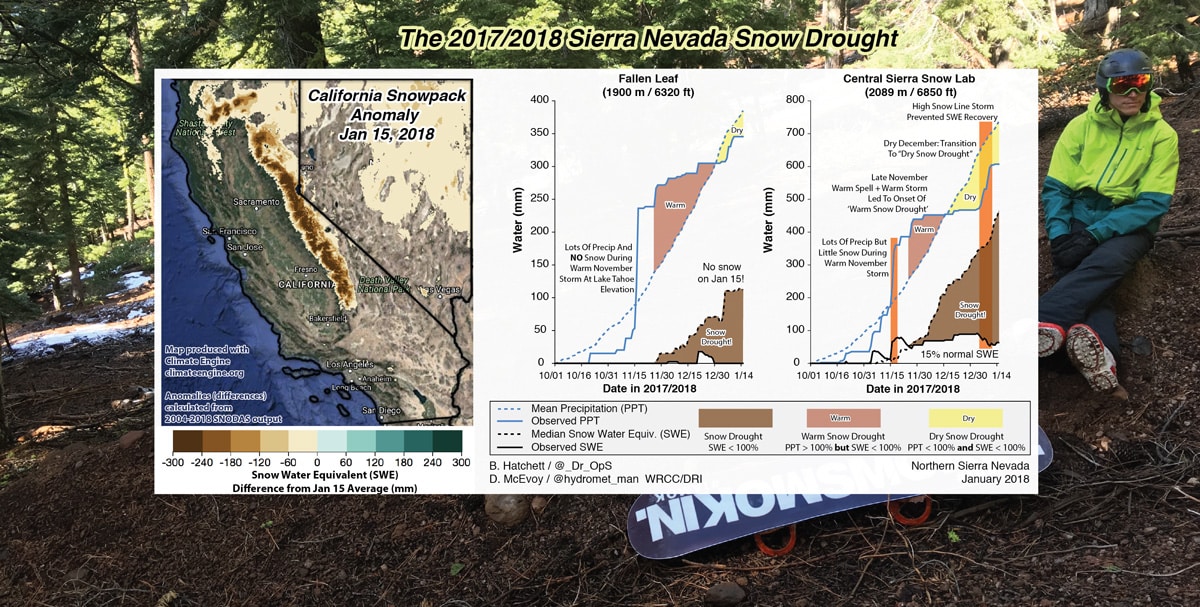

The snow drought of 2017/2018 as observed at Fallen Leaf Lake, Calif. and the Central Sierra Snow Lab in Soda Springs, Calif. Map created by ClimateEngine.org – Powered by Google Earth Engine. Credit Benjamin Hatchett, DRI.

Previous research has used April 1st (the date that snowpack levels, measured as snow water equivalent or SWE, in the Sierra Nevada typically reach a maximum) as the primary date for calculating snow drought, and classified each snow drought as one of two types, warm or dry. “Warm snow drought” years were characterized by above-average levels of precipitation and below-average snow accumulation (SWE); “Dry snow drought” years were characterized by below-average levels of precipitation and below-average snow accumulation (SWE).

Hatchett and McEvoy’s work expanded upon these concepts by examining the progression of snow droughts throughout the entire winter season.

Their results illustrate that each snow drought originates and develops along a different timeline, with some beginning early in the season and some not appearing until later. Snow droughts often occurred as a result of frequent rain-on-snow events, low precipitation years, and persistent dry periods with warmer than normal temperatures. The severity of each snow drought changed throughout the season, and effects were different at different elevations.

“We learned that if you just look at snow levels on April 1st, you miss out on a lot of important information,” McEvoy said. “For example, if you are in a snow drought all winter long and come out of it right at the end due to a few big storms, there are probably implications to that.”

Sometimes, McEvoy explained, snow droughts were found to occur in years with above-average precipitation. For example, in 1997, a powerful atmospheric river storm event led to record-breaking flooding throughout the region – but much of the moisture arrived as rain rather than snow, with detrimental effects on the snowpack.

Climate change is likely to make snow drought an even more common phenomenon in the future, said Hatchett, as temperatures in the northern Sierra Nevada are expected to continue warming.

“There has always been an occasional snow drought year in the mountains, but that was typically the ‘dry’ type of snow drought caused by lack of precipitation,” Hatchett said. “As the climate grows warmer and more precipitation falls as rain instead of snow, we are seeing that we can have an average or above-average precipitation year and still have a well below-average snowpack.”

The implications of snow drought have not yet been studied extensively, but may include impacts to water resources, snowmelt runoff, flooding, soil moisture, tree mortality, ecological system health, fuel moisture levels that drive fire danger, human recreation, and much more. In regions such as the Lake Tahoe Basin, where mountain snowpack sustains wildlife, ecosystems, local economies, and provides crucial water resources to downstream communities throughout the year, the impacts of snow droughts could be enormous.

The last four winters, Hatchett and McEvoy noted, have all exhibited some degree of snow drought in the northern Sierra Nevada. Even the recent huge winter of 2016/17, which ended with far above-average snowpack levels (205% of the long-term median on April 1, 2017 in the Lake Tahoe Basin), began with a period of early-season snow drought during a dry November. This winter has been no exception, with snow drought taking hold over low elevation areas in November, and moving to higher elevation sites in December.

Only time will tell how the 2017/2018 winter season will end, but in the meantime, snow drought is affecting the region in ways that have not yet been fully quantified.

Hatchet and McEvoy hope that their research will prompt further investigations into the potentially devastating impacts of snow drought, and will help to inform regional climate adaptation planning efforts.

“We spend a lot of time going out and skiing, climbing, and hiking in the mountains, which is what inspired us to study these things,” Hatchett said. “We’re seeing and experiencing snow drought first-hand, and we have to quantify it and understand it because these are changing patterns on the landscape that will have massive implications for the mountain environments that we experience each day and the mountain communities that we live in.”

The full version of the study—“Exploring the Origins of snow drought in the northern Sierra Nevada, California”—is available online at –http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/EI-D-17-0027.1

###

The Desert Research Institute (DRI) is a recognized world leader in investigating the effects of natural and human-induced environmental change and advancing technologies aimed at assessing a changing planet. For more than 50 years DRI research faculty, students, and staff have applied scientific understanding to support the effective management of natural resources while meeting Nevada’s needs for economic diversification and science-based educational opportunities. With campuses in Reno and Las Vegas, DRI serves as the non-profit environmental research arm of the Nevada System of Higher Education. For more information, please visit www.dri.edu.