Heading to the Mountains?

RENO, NEV.

By Kelsey Fitzgerald

Snow Algae

Citizen Science

Featured research by DRI’s Alison Murray, Meghan Collins, Jaiden Christopher, Eric Lundin, and Sonia Nieminen.

On a cool and breezy morning in late spring, DRI Research Professor Alison Murray, Ph.D. and student intern Sonia Nieminen hiked up a ski slope at Mount Rose Ski Area, outside of Reno. The ground, wet from snowmelt, squished and squelched beneath their feet as they crossed a hillside of soggy grass to reach a remnant patch of late-season snow.

They were out to find snow algae – a type of freshwater algae that thrives in late-season snowpack. Although snow algae is best known for being pink, it actually comes in colors ranging from yellow to orange, light-green, brown, light pink, or a bright watermelon pink.

“There’s a whole microbial community that lives in the snow, and snow algae is the food source that gets it all started,” Murray explained. “They are a primary producer, so they bring organic carbon into the snow that feeds a diverse community of bacteria, fungi, protozoans and other multicellular animals. For example, little rotifers, tartigrades, mites, and spiders also call the snow ecosystem home.”

Murray, Nieminen, Meghan Collins, Jaiden Christopher, and Eric Lundin at DRI are studying snow algae as part of the Living Snow Project (https://wp.wwu.edu/livingsnowproject/) – a collaboration between DRI and Robin Kodner and her team at Western Washington University. The project aims to learn more about the ecology, diversity, and prevalence of snow algae in the Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountains, with help from citizen scientists.

“The literature is pretty spotty on the biology of snow and snow algae,” Murray said. “A lot is known about just a few species of snow algae, but we want to see what else is out there, and learn more about the role that algae play in the snowpack in a changing climate.”

Alison Murray digs into a patch of light pink snow at Mount Rose Ski Area to collect a snow algae sample.

Top Right: Snow algae samples are collected using a plastic tube filled with a small amount of preservative.

Bottom: Sonia Nieminen collects a snow algae sample at Mount Rose Ski Area.

Top Right: Sonia Nieminen collects a snow algae sample at Tahoe Meadows. Rubber gloves help to prevent the contamination of samples with any microbiota on the researcher’s hands.

Bottom: Samples tubes containing snow algae collected at Tahoe Meadows in Nevada during late spring 2022.

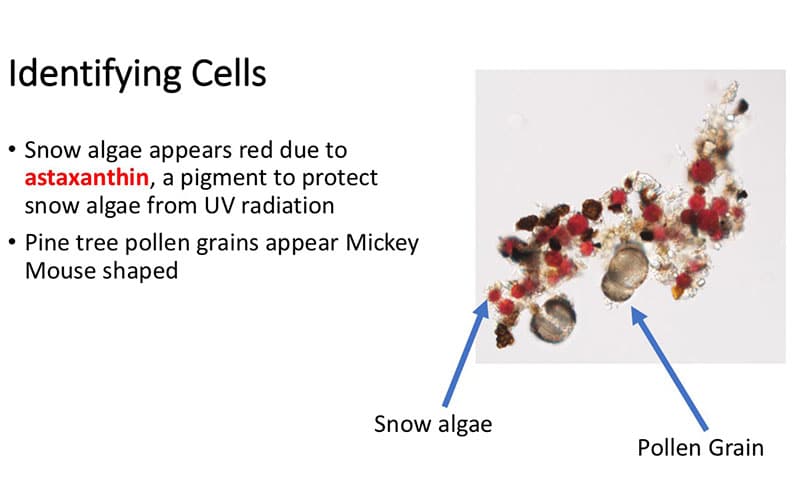

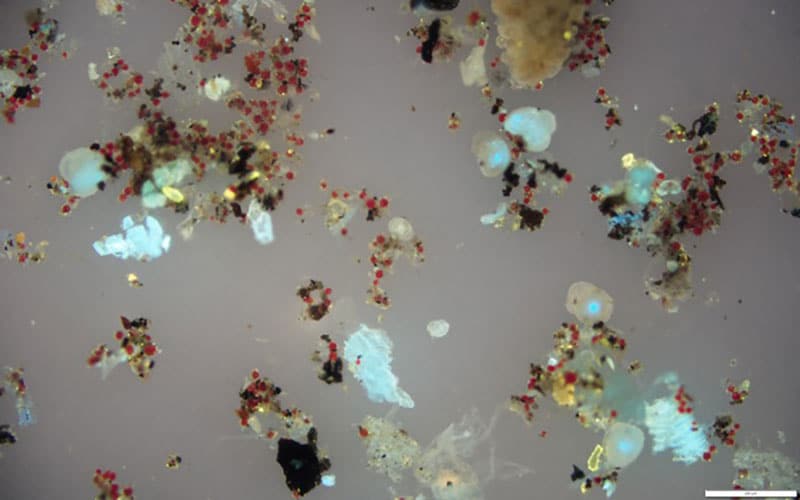

“The algae appear red due to astaxanthin, a pigment that protects snow algae from UV radiation,” Lundin explained.

Next, he examined the samples using fluorescence microscopy and DAPI staining. DAPI is a fluorescent dye that is attracted to DNA. Using fluorescence microscopy, the snow algae appear as red circular cells due to the autofluorescence of chlorophyll.

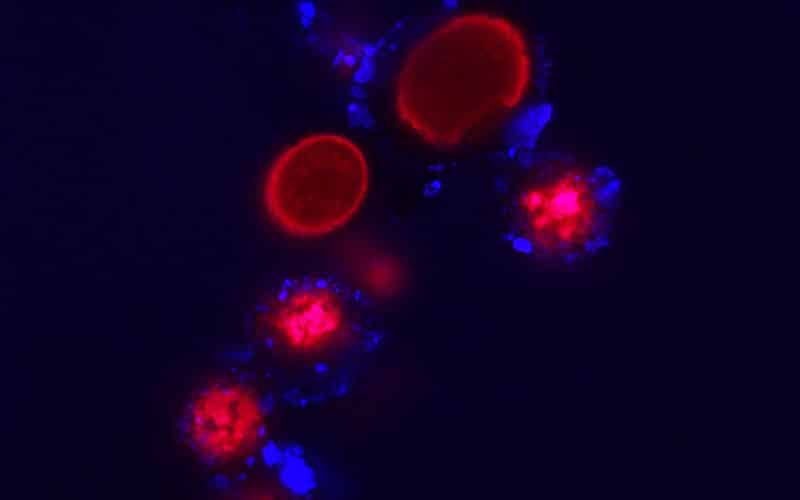

Finally, he looked at the samples using confocal microscopy, which uses specific wavelengths of light to induce fluorescence and shows the 3-D structure of the cells as a 2-D image. In these images, blue indicates the presence of DNA. Chlorophyll appears red, clearly showing the presence of snow algae. The snow algae cells are often coated with a layer of bacterial cells, and some debris too.

Top Right: Using fluorescence microscopy and DAPI staining to examine a sample, snow algae appear as red circular cells. Pollen grains, if the nucleus is still intact, emit blue light due to the presence of DNA. Other material seen in the image is a combination of bacteria, plants, dirt, and extracellular material.

Bottom: Snow algae, some of which are surrounded by bacterial cells (blue) as viewed with confocal microscopy. Blue indicates the presence of DNA, and red indicates presence of chlorophyll.

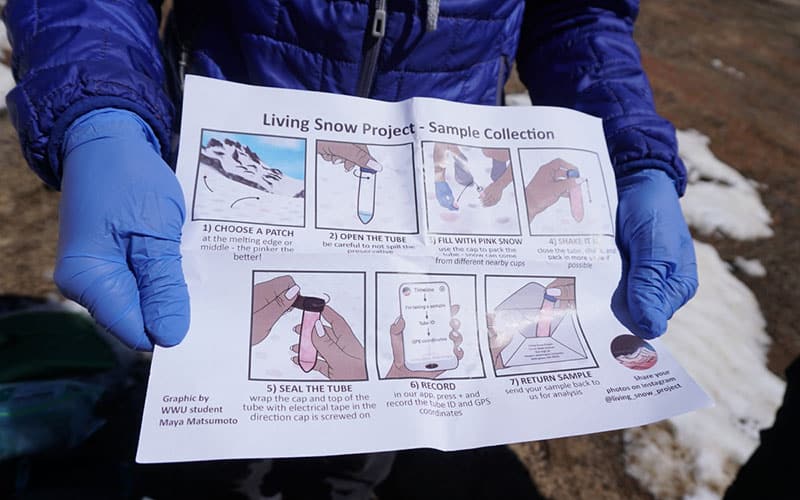

Want to participate in the Living Snow Project?

For the second year in a row, the group has put out a call to action to the outdoor recreation community for help tracking snow algae blooms, recording observations, and collecting samples of snow algae from backcountry areas during the late spring into the summer. By enlisting the help of volunteers, the research team is able to cover much more ground than they could alone.

“We appreciate the help of anyone who is out in the mountains in the early summer – hikers, summer skiers, or anyone else – who can help us collect samples or just use their phones to log locations where snow algae is found and how prevalent it is,” Murray said.

Are you heading to the mountains and interested in participating in the Living Snow Project? Instructions for how to participate are available on the Living Snow website: https://wp.wwu.edu/livingsnowproject/

About DRI

The Desert Research Institute (DRI) is a recognized world leader in basic and applied environmental research. Committed to scientific excellence and integrity, DRI faculty, students who work alongside them, and staff have developed scientific knowledge and innovative technologies in research projects around the globe. Since 1959, DRI’s research has advanced scientific knowledge on topics ranging from humans’ impact on the environment to the environment’s impact on humans. DRI’s impactful science and inspiring solutions support Nevada’s diverse economy, provide science-based educational opportunities, and inform policymakers, business leaders, and community members. With campuses in Las Vegas and Reno, DRI serves as the non-profit research arm of the Nevada System of Higher Education. For more information, please visit www.dri.edu.