With support from the Nevada Governor’s Office of Economic Development, TuBiomics has emerged as a leader in developing plant and soil health products using sustainable, natural, chemistry-based solutions.

DRI Scientists Launch Nevada Orchid Project

DRI scientists are starting the first ever effort dedicated to studying and conserving Nevada’s orchids. Many people know orchids as flashy, delicate flowers raised in lush greenhouses, but orchids also thrive in the sparse wetlands sprinkled around Nevada’s arid landscape. In fact, lovers of the state’s orchids like to tout one impressive statistic: Nevada has no less than 14 species of native orchids, in contrast with Hawaii’s mere three.

Lynn Fenstermaker: Celebrating a Career in Ecological Remote Sensing and NASA Space Grant Leadership

Lynn Fenstermaker, Ph.D., recently retired from DRI after 32 years. She studied large-scale questions about environmental stressors.

Estom Yumeka Maidu Student Teaches DIY Air Filtration Techniques to Help Reservation Communities During Wildfire Season

Many houses have no particulate filtration systems, especially on reservations. Piercen Nguyen and his colleagues have a proven solution.

Tim Minor: Celebrating a Career in GIS and Remote Sensing

Tim Minor, M.A, recently retired from DRI after 31 years. His successful career as a geographic information systems (GIS) and remote sensing scientist brought him to DRI in 1991.

Scientists Uncover Conditions Key to Formation of the Great Barrier Reef

Scientists have sought to understand the conditions that led to the Great Barrier Reef’s formation. A new study claims to have the answer.

Footprints Claimed as Evidence of Ice Age Humans in North America Need Better Dating, New Research Shows

Recent research claimed that preserved footprints were from the last ice age. Now, a new study disputes the evidence of such an early age.

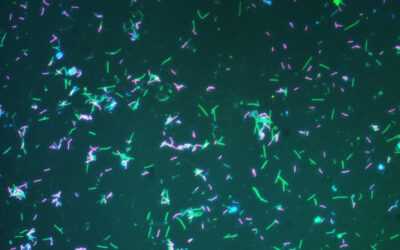

Scientists Unveil New System for Naming Majority of the World’s Microorganisms

Scientists presented a new system, the SeqCode, that could help microbiologists effectively categorize and communicate about microorganisms.

Restoring our relationship with hímu (willow) requires human interaction rather than protection

The continuation of life for the Wá∙šiw is based around plants like hímu. With it, they can help us understand our problems.

“Buen Aire Para Todos” project will create a new air quality monitoring system for Latinx community in East Las Vegas

Latinx communities in East Las Vegas will soon have access to an improved air quality monitoring program, thanks to a EPA grant for a new project called Buen Aire Para Todos.