Featured research by DRI’s Kristin VanderMolen, Ben Hatchett, Erick Bandala, and Tamara Wall

Above: Aerial view of California’s Imperial Valley, where daytime temperatures during summer months can reach as high as 120 degrees. Credit: Thomas Barrat/Shutterstock.com

In July and August, daytime temperatures along parts of the US-Mexico border can reach as high as 120 degrees – more than 20 degrees above normal human body temperature. For agricultural workers and others who live and work in the region, exposure to these extreme high temperatures can result in serious health impacts including heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and heat-related death.

Although the National Weather Service and public health organizations issue heat warnings to communicate risk during extreme heat events, heat-related illness and death are still common among vulnerable populations. Now, a group of DRI scientists led by Kristin VanderMolen, Ph.D., Assistant Research Professor with DRI’s Division of Atmospheric Sciences, is trying to figure out why.

“With the continued increase in episodes of extreme heat and heat waves, there has been an increase in warning messaging programs, yet there continue to be high numbers of heat-related illness and death in communities along the US-Mexico border,” VanderMolen said. “So, there’s this question – if agencies are doing all of this messaging, and people are still getting sick and even dying, then what’s going on?”

An agricultural field in California’s Imperial Valley, where DRI researchers are exploring questions about heat messaging and vulnerability in populations of agricultural workers and others who are vulnerable to heat-related illness and death.

Credit: Winthrop Brookhouse/Shutterstock.com

Assessing heat messaging: An interdisciplinary approach

In 2018, VanderMolen and colleagues Ben Hatchett, Ph.D., Erick Bandala, Ph.D., and Tamara Wall, Ph.D. received funding from NOAA’s International Research and Applications Project (IRAP) to explore questions about heat messaging and vulnerability in two pairs of US-Mexico border cities, San Diego-Tijuana and Calexico-Mexicali. Collectively these areas form the boundaries of the Cali-Baja Bi-national Megaregion. This unique transboundary location integrates the economies of the United States and Mexico, exporting approximately $24.3 billion worth of goods and services each year.

With expertise in the areas of anthropology, meteorology, climatology, and population health, this interdisciplinary team of researchers is now working on this problem from several angles. They are using climate data to characterize and assess past heat extremes as well as using long-range weather forecasts and climate projections to help improve the ability to put out advance messaging about future heat waves. They are working to identify and map populations that are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat and are collaborating with local agencies to understand why people may or may not take protective action during heat waves.

From initial conversations with local civic organizations and public health agencies, the team has learned that the reasons people may not be following heat warnings are complex. Recommended actions such as “stay indoors and seek air-conditioned buildings,” or “take longer and more frequent breaks,” may not be realistic for agricultural workers or others who don’t have access to air-conditioned spaces. There can even be negative consequences for those who choose to seek medical help.

“A big piece of the story that we’ve heard from some of the independent groups that work with agricultural workers in the region is that if someone gets sick and doesn’t show up for work, they can lose their job,” Hatchett explained. “If they go to the hospital and somebody sees them or hears about it, they can lose their job. There are some really big issues related to people not feeling okay with trying to get the help they need.”

“There is evidence to suggest that cases of heat-related illness and death are underreported, probably severely underreported,” VanderMolen added. “The demographics of the individuals for documented cases don’t reflect the population demographics overall. We know that there are a lot of inequalities in that area that may get in the way of people reporting illness.”

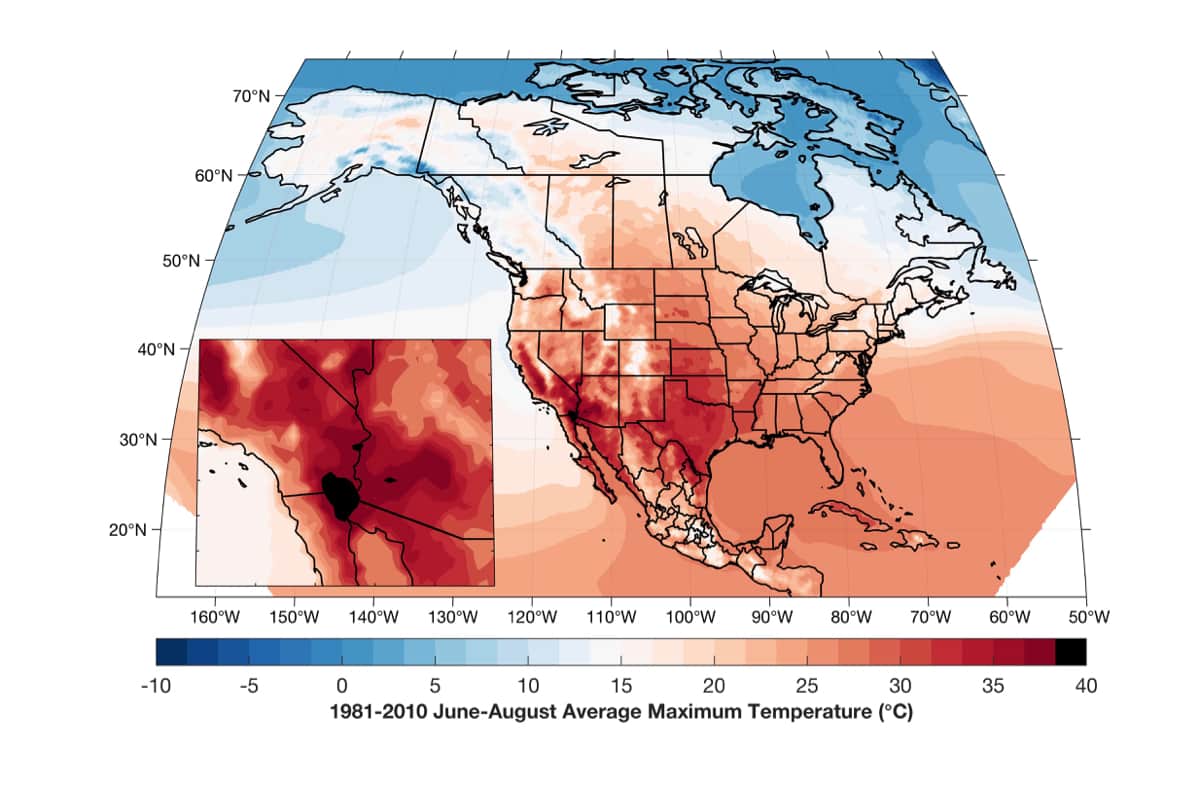

A map of summer maximum near-surface temperatures over the 30-year period from 1981–2010 shows that Imperial Valley (at the border between Mexico and the southeastern corner of California) is the hottest place in in North America, with an average maximum temperature from June to August of 40° Celsius (104° Fahrenheit). Data is from the North American Regional Reanalysis.

Credit: Ben Hatchett/DRI

COVID-19 complications and next steps

Originally, VanderMolen was planning to travel to the US-Mexico border this summer to do one-on-one interviews with members of vulnerable populations, but the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in unforeseen complications.

Imperial County has been hit very hard by COVID-19, compounding the effects of extreme heat for the vulnerable populations that VanderMolen and her team hope to work with. The pandemic has also made it unfeasible to travel to the region to do face-to-face interviews, and has created challenges in coordinating with local agencies that are now overwhelmed in their efforts to address COVID-19.

“It’s a really interesting place and time to do this work because there are questions about what it means to be on stay-at-home orders and limited travel orders when it’s 114 degrees outside and you don’t have reliable air conditioning or its cost is prohibitive,” VanderMolen said. “At the same time, because they’re so overwhelmed right now with caseload, most folks in the area can’t really afford to address issues beyond COVID-19.”

As the research team works to navigate a path forward that is safe for both the interviewers and interviewees, they remain committed to developing information that will help vulnerable populations along the border.

“I hope that the information we provide is something decision-makers can use to make the right decision or create legislation that can help protect workers in the field, or at least call attention to the kind of inequalities and risk that the people there are being exposed to,” Bandala said. “Or, if we can produce information to change the mindset of the people to start thinking of themselves as a population at risk, and put more attention on the heat warnings, that will suffice for me to feel satisfied with the results of our research.”

The US-Mexico border is just one of many places around the globe where heat-related illness is a problem, added Hatchett – and many of those places happen to be where a lot of our food is grown or where important industries are located.

“I think this is a somewhat ubiquitous problem around the planet. We have these really important places that are susceptible to environmental extremes and these people that we rely on to have these regions be productive in terms of agriculture or industry. Unfortunately, those people are often the most susceptible and underserved populations to these compound environmental hazards,” Hatchett said. “It’s so easy to forget them, but one of the goals of this project is really to bring to light the importance of aiming much-needed resources at trying to help those populations and those places.”

Additional information

For more information on the members of this DRI research team, please visit:

- Kristin VanderMolen (Directory Profile)

- Erick Bandala (Directory Profile)

- Tamara Wall (Directory Profile)

This research was supported by NOAA’s International Research and Applications Project (IRAP).