A new study shows that tailpipe emissions are declining, but brake and tire wear particle emissions remain a persistent – and unregulated – air quality concern

Air pollution near roads remains a significant health concern in the U.S., with an estimated 60 million people living within 500 meters of a major highway. Even as emissions from engine exhaust decline with stringent regulations and the growing popularity of electric vehicles, other traffic-related pollution remains unaddressed. Of particular concern are the microscopic particles from brakes and tires, worn down from abrasion and degradation, which mix into the air we breathe and wash into our watersheds, creating hazards for human and environmental health.

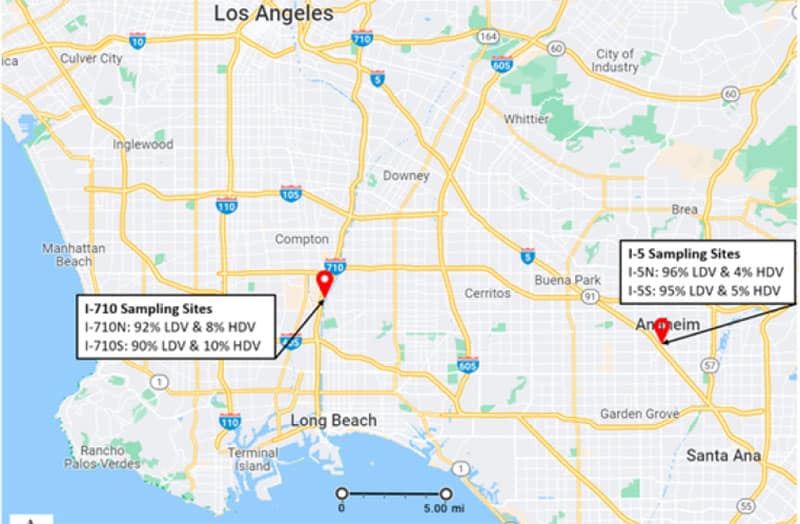

In a new study published Nov. 23 in Environmental Pollution, researchers from DRI, UC Riverside, UNLV, and the California Air Resources Board take a closer look at these overlooked pollutants, known as non-tailpipe emissions. With funding from the California Air Resources Board, they placed air quality monitors near two southern California highways and found that air pollutants from brake and tire wear exceed those from engine exhaust.

“We knew that tailpipe emissions are coming down, and that non-tailpipe emissions have been steady or slightly increasing,” says Xiaoliang Wang, Ph.D., Research Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at DRI and the study’s lead author. “But I didn’t realize that it’s already crossing over – that was a surprise.”

Map of roadside sampling locations in Los Angeles, California — one of the most polluted areas in the U.S.

Credit: Elyse DeFranco/DRI.

Tire wear particles contain rubber and microplastics, as well as thousands of chemicals, some of which are known ecological hazards. Previous research identified one of these chemicals as the primary culprit in the decline of Coho salmon in the Pacific Northwest. And brake pads contain metals and other materials known to be harmful to human health. Non-tailpipe emissions like brake and tire wear particles aren’t regulated the way engine exhaust is, and are expected to become the primary source of particulate matter pollution near roads.

“There is increasing interest in understanding how much non-tailpipe emissions – including brake wear, tire wear, road surface wear, and road dust – are impacting air pollution for people living close to roadways,” Wang says. “This has environmental justice implications as well because many low-income communities tend to live closer to roads.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established a near-road air monitoring network that measures nitrogen dioxide (which causes respiratory tract damage and can trigger asthma), but fine and coarse particles that are more related to non-tailpipe emissions than engine exhaust are monitored spottily or not at all.

California has led the way in enacting regulations on exhaust emissions, as Los Angeles first began experiencing smog-choked air in the 1940s. It wasn’t until the early 1950s that scientists discovered that motor vehicles were the primary source of this smog, and that engine exhaust chemically reacts with sunlight and industrial air pollution to create what is known as “secondary pollutants.” This means that air pollution isn’t merely the combination of all added pollutants, but that as these pollutants intermix in the air, new pollutants are born.

Electric vehicles have eliminated tailpipe emissions by transferring their emissions to their power source, but are heavier than conventional gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles. This could mean more road and tire wear particle emissions.

“There’s still active research going on trying to understand what’s the impact of electrification of vehicles on non-tailpipe emissions,” Wang says. Previous research has noted that because electric vehicles don’t reduce non-tailpipe particulate matter emissions, they shouldn’t be considered as the single and only solution to urban air pollution.

Although this study focused on air pollution near roads, Wang notes that the pollutants don’t stay only near highways, but follow wind patterns to become part of the overall air pollution mix, and eventually get washed into storm gutters and out to sea.

The study team is continuing this research to better understand the chemicals in the air samples they collected and will publish a more detailed analysis of the sources. The information will be provided to appropriate environmental and transportation agencies to aid decision-making for air quality improvements.

Evidence of non-tailpipe emission contributions to PM2.5 and PM10 near southern California highways

Environmental Pollution

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120691

Study authors include DRI researchers Xiaoliang Wang, Steven Gronstal, Judith C. Chow, Steven Sai Hang Ho, and John G. Watson; UC Riverside researchers Brenda Lopez, Guoyuan Wu, and Heejung Jung; UNLV researcher L.-W. Antony Chen; and Qi Yao and Seungju Yoon of the California Air Resources Board.