In a new study, researchers take a closer look at some overlooked pollutants, known as non-tailpipe emissions.

DRI project contributes to an air quality win in Jakarta

This fall, DRI scientists received word that air quality monitoring guidelines and reports from a decade-old project in Indonesia had served a beneficial new purpose: providing key evidence in an important court decision that will require stricter air quality standards in the City of Jakarta.

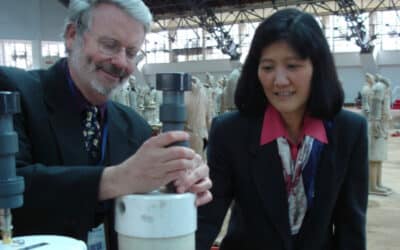

DRI Air Quality Experts Awarded Prestigious Haagen-Smit Prize

April 30, 2020 (RENO) – Drs. Judith Chow and John Watson, research professors in the Division of Atmospheric Sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, were awarded Elsevier Publisher’s 2019 Haagen-Smit Prize for outstanding paper published in the journal...