Reno, Nev. (Nov. 13, 2018): A new ice core record from the French Alps shows impacts of fossil fuel emissions in the form of a steep increase in iodine levels during the second half of the 20th century, according to a study released this week by an international team of scientists from the Université Grenoble Alpes-CNRS of France, the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Reno, Nev., and the University of York in England.

“Model and laboratory studies had suggested that atmospheric iodine should have increased during recent decades as a result of increasing fossil fuel emissions but few long-term records of iodine existed with which to test these model findings, and none in Western Europe where modeled iodine increases were especially pronounced,” said French researcher and lead author Michel Legrand, Ph.D.

Iodine is an important nutrient for human health, key in the formation of thyroid hormones. It is present in ocean waters, and is released into the atmosphere when Iodide (I-) reacts with ozone (03) at the water’s surface. From the atmosphere, iodine is deposited onto Earth’s land surfaces, and absorbed by humans in the foods that we eat.

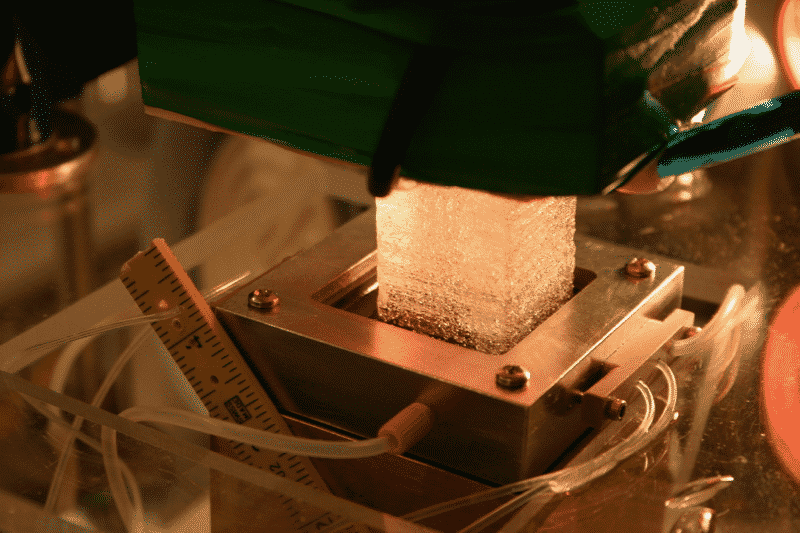

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was initiated after scientists observed a three-fold increase in iodine between 1950 and the 1990s measured in an ice core from the Col du Dome region of France. The core was collected by French scientists and analyzed in 2017 in DRI’s Ultra Trace Ice Core Analysis Laboratory.

Researchers examine an ice core sample drilled from Mont Blanc. Credit: B. Jourdain, L’Institut des Géosciences de l’Environnement.

Although previous modeling simulations had indicated a similar increase in global iodine emissions during the 20th century, this new record provides the first ice core iodine record from outside of the polar regions.

“Iodine has been measured previously in polar ice cores but changes there largely can be attributed to variations in sea ice,” said Joe McConnell, Ph.D., research professor of hydrology and head of DRI’s ice core laboratory. “These variations mask the larger scale trends linked to fossil fuel emissions and changes in ozone chemistry. Our new iodine record extends from 1890 to 2000 and is from the French Alps, a part of the world where there are no sea ice influences.”

As part of this study, more than 120 meters (nearly 400 feet) of ice core from the French Alps was analyzed for iodine and a broad range of chemical species by a group of DRI researchers that included McConnell, Monica Arienzo, Ph.D., Nathan Chellman, and Kelly Gleason, Ph.D., using DRI’s unique continuous analytical system.

The study team then analyzed the ice core record alongside modeling simulations to investigate past atmospheric iodine concentrations and changes in iodine deposition across Europe. According to their results, the observed tripling of iodine levels in the ice during the 1950s to 1990s were caused by increased iodine emissions from the ocean.

An ice core sample is processed in DRI’s Ultra-Trace Ice Core Laboratory in Reno, Nev. Credit: Joe McConnell/DRI.

Ozone in the lower atmosphere acts as an air pollutant and greenhouse gas. Because iodine emissions from the ocean occur when iodine in the water reacts with ozone in the lower atmosphere, the study results indicate that increased ozone levels are increasing the availability of iodine in the atmosphere – and also that iodine is helping to destroy this “bad” ozone.

“Iodine’s role in human health has been recognized for some time – it is an essential part of our diets,” said Lucy Carpenter, Ph.D., Professor with University of York’s Department of Chemistry. “Its role in climate change and air pollution, however, has only been recognized recently and the impact of iodine in the atmosphere is not currently a feature of the climate or air quality models that predict future global environmental changes.”

According to the World Health Organization, iodine deficiency remains a significant health problem in parts of Europe, including France, Italy and certain regions of Spain – regions that now appear to have received a boost in iodine levels in recent years.

“The silver lining in the findings of this study is that the increase in human-caused pollution during the latter half of the 20th century may be leading to an increase in the availability of iodine as an essential nutrient,” Legrand said.

###

To view the study, titled Alpine ice evidence of a three-fold increase in atmospheric iodine deposition since 1950 in Europe due to increasing oceanic emissions, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on 12 November 2018, please visit: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/11/07/1809867115

Samantha Martin from the University of York contributed to this release.

The Desert Research Institute (DRI) is a recognized world leader in basic and applied interdisciplinary research. Committed to scientific excellence and integrity, DRI faculty, students, and staff have developed scientific knowledge and innovative technologies in research projects around the globe. Since 1959, DRI’s research has advanced scientific knowledge, supported Nevada’s diversifying economy, provided science-based educational opportunities, and informed policy makers, business leaders, and community members. With campuses in Reno and Las Vegas, DRI serves as the non-profit research arm of the Nevada System of Higher Education. Learn more at dri.edu, and connect with us on social media on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.