Researchers at the University of Nevada, Reno in collaboration with Henry Sun of the Desert Research Institute and Christopher McKay of the NASA Ames Research Center received a NASA Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) seed grant to study how they can mimic biology to make some powerful sunscreen.

Meet Charlotte van der Nagel, Graduate Researcher

Charlotte van der Nagel is a graduate research assistant with the Division of Earth and Ecosystems Sciences at DRI in Las Vegas and a Ph.D. student in the Geoscience program at University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

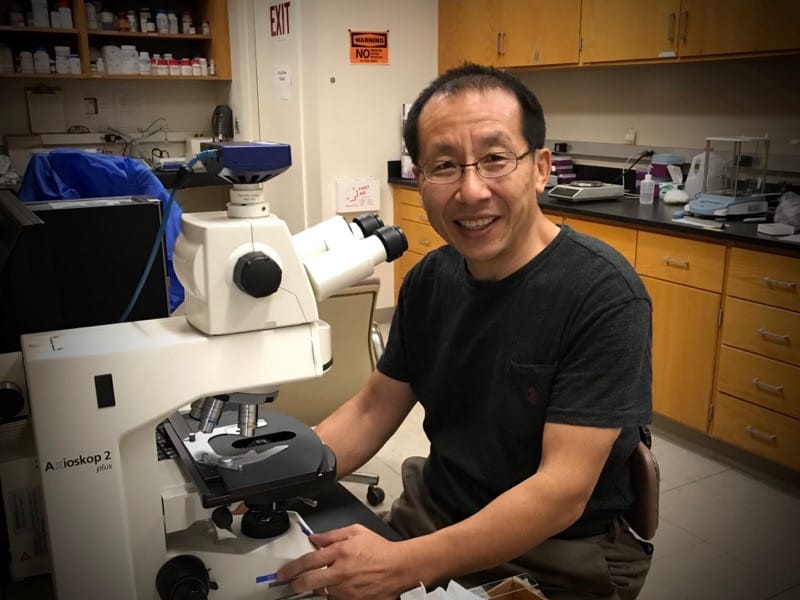

Meet Henry Sun, Ph.D.

Henry Sun, Ph.D., is an associate research professor of microbiology with the Division of Earth and Ecosystem Sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Las Vegas. Henry specializes in the study of microscopic organisms that live in extreme environments, often using...

Saving the Desert’s Upper Crust

To a casual observer, desert lands may appear a barren vista of sand and soil, sparsely dotted with shrubbery and cacti but, in reality, they are lush with microscopic plants: lichens, mosses, and cyanobacteria. There isn’t an inch of soil that is without these...