The new study helps illuminate how changes in forest composition followed European settlement and natural changes in climate.

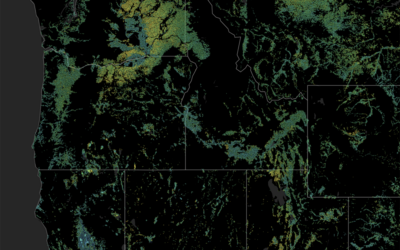

New Study Reveals Impacts of Irrigation and Climate Change on Western Watersheds

DRI’s Justin Huntington coauthored the new study, led by researchers at the University of Montana and the Montana Climate Office, which published mid-December in the Nature Journal, Communications Earth and Environment.

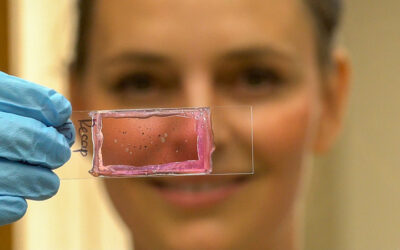

A New, Rigorous Assessment of OpenET Accuracy for Supporting Satellite-Based Water Management

A new study offers a comprehensive multi-model, large-scale accuracy assessment of an operational satellite-based data system to compute evapotranspiration. The researchers found that OpenET data has high accuracy for assessing evapotranspiration in agricultural settings, particularly for annual crops like wheat, corn, soy, and rice.

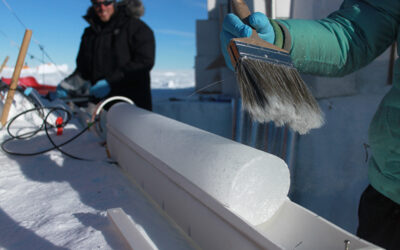

The First Assessment of Toxic Heavy Metal Pollution in the Southern Hemisphere Over the Last 2,000 Years

An international team of scientists led by DRI found evidence of Southern Hemisphere heavy metal pollution preserved in Antarctic ice cores from early Andean cultures and Spanish Colonial mining that predates the Industrial Revolution by centuries.

Climate Change Will Increase Wildfire Risk and Lengthen Fire Seasons, Study Confirms

Scientists examined multiple fire danger indices for the contiguous U.S. to assess the impact of climate change on future wildfire risk and seasonality.

3000 years of carbon monoxide records show positive impact of global intervention in the 1980s

An international team of scientists have assembled the first complete record of carbon monoxide concentrations in the southern hemisphere, based on measurements of air.

Volcanic Eruptions Triggered Historical Global Cooling

The new study, led by the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at St Andrews with international colleagues from the Desert Research Institute and others in Switzerland and the USA, and published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) (6 November 2023), finds that massive volcanic eruptions caused historical global cooling.

Scientists Map Loss of Groundwater Storage Around the World

A new study maps, for the first time, the permanent loss of aquifer storage capacity occurring globally. Researchers from DRI, Colorado State University, and the Missouri University of Science and Technology examined how groundwater extraction is driving land subsidence and aquifer collapse.

Childhood Traumas Strongly Impact Both Mental and Physical Health

Most Americans report experiencing at least one childhood trauma and these experiences have significant impacts on our health as adults.

Childhood trauma and genetics linked to increased obesity risk

New research from the Healthy Nevada Project® found that participants with specific genetic traits and who experience childhood traumas are more likely to suffer from adult obesity.