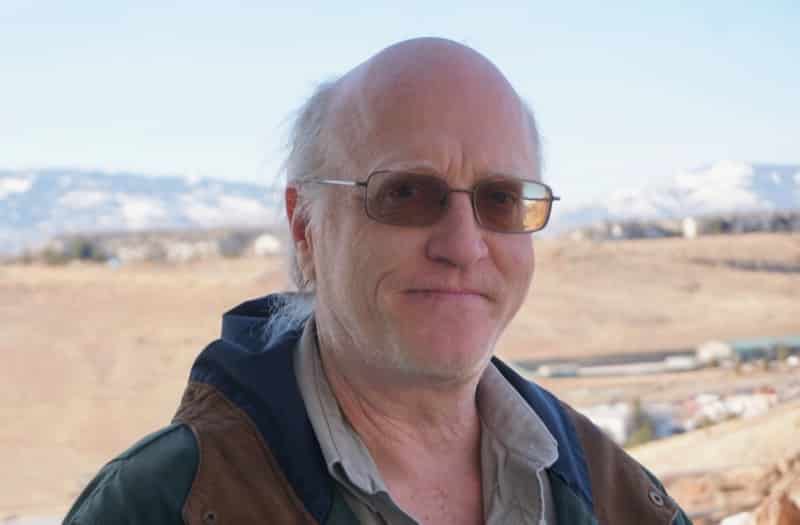

Ken McGwire, Ph.D., is an associate research professor of geography with the Division of Earth and Ecosystem Sciences at the Desert Research Institute.

Research team develops first lidar-based method for measuring snowpack in mountain forests

Reno, Nev. (Jan. 22, 2018): Many Western communities rely on snow from mountain forests as a source of drinking water – but for scientists and water managers, accurately measuring mountain snowpack has long been problematic. Satellite imagery is useful for calculating...