The new study helps illuminate how changes in forest composition followed European settlement and natural changes in climate.

Field Notes From DRI’s Ice Core Team in Greenland: A Story Map

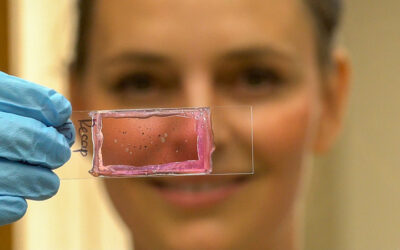

A team of DRI scientists returned to Greenland in May 2023, where they are drilling a 150m long ice core to study interactions between ice chemistry and microbial life.

Field Notes From a DRI Research Team in Greenland: A Story Map

In May 2022, a team led by scientists from DRI in Reno, Nevada departed for Greenland, where they plan to collect a 440 meter-long ice core that will represent 4,000 years of Earth and human history.

Study shows a recent reversal in the response of western Greenland’s ice caps to climate change

Although a warming climate is leading to rapid melting of the ice caps and glaciers along Greenland’s coastline, ice caps in this region sometimes grew during past periods of warming, according to new research published today in Nature Geoscience.

Meet Nathan Chellman, Ph.D.

Meet DRI scientist Nathan Chellman and learn about his work in the Ice Core Laboratory in this interview with DRI’s Behind the Science Blog.