DRI’s annual awards and recognition ceremonies were held at our Reno and Las Vegas campuses in early October to honor scientists and staff members for their achievements. Along with the below awardees, several faculty and staff were recognized for their long-term service to the institute. DRI prides itself on fostering a fulfilling workplace that builds internal community and inspires scientific discovery.

Western Agricultural Communities Need Water Conservation Strategies to Adapt to Future Shortages

Relying on water storage won’t be enough to make up for declines in future water availability under a changing climate, new study shows. Beatrice Gordon, lead author of the study and sociohydrologist and postdoctoral researcher at DRI, says the research is needed to inform water management at the local level, where most decisions are made.

Rising Temperatures Will Significantly Reduce Streamflow in the Upper Colorado River Basin As Groundwater Levels Fall, New Research Shows

Climate change will dramatically impact streamflow and its contributions to the Colorado River by increasing forest water use and reducing groundwater levels, new study finds.

As climate warms, summer monsoons to produce less streamflow

A new paper led by DRI’s Rosemary Carroll points to both the importance of monsoon rains in maintaining the Upper Colorado River’s water supply and the diminishing ability of monsoons to replenish summer streamflow in a warmer future with less snow accumulation.

Meet Rosemary Carroll, Ph.D.

Rosemary Carroll, Ph.D., is an associate research professor in DRI’s Division of Hydrologic Sciences.

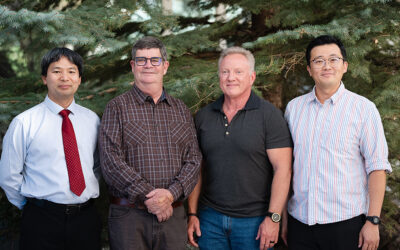

DRI faculty teach water, sanitation, hygiene, and environmental issues courses in eSwatini (Swaziland)

Students from DRI’s WASH Capacity Building Program learn about dry sanitation during a field trip to the University of eSwatini (Swaziland) project site at the community of Buka, eSwatini. September 2018. Credit: Braimah Apambire/DRI. In August and early...