DRI’s Behind the Science Blog continues with the second installment of our fall 2022 Research Immersion Internship Series

This fall, DRI brought eleven students from Nevada’s community and state colleges to the Las Vegas and Reno campuses for a paid, immersive research experience. Over the course of the 16-week program, students worked under the mentorship of DRI faculty members to learn about the process of using scientific research to solve real-world problems.

Our Behind the Science Blog is highlighting each research team’s accomplishments over a series of five stories. Click here to read the first installment in our internship series.

In this story, we follow Tiffany Pereira’s student interns as they track elusive and threatened desert tortoises in the Las Vegas desert.

A desert tortoise in Mojave National Preserve.

Credit: Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service.

Student Researchers: Amelia Porter and Akosua Fosu

Faculty Mentor: Tiffany Pereira, M.S., Ecologist and Assistant Research Scientist

Despite their enormous size, desert tortoises are elusive desert dwellers, often spending most of their lives in underground burrows – giving them their scientific name, Gopherus agassizii. They occur across the Mojave and Sonoran deserts of California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act since 1990, their numbers are declining due to a number of threats. Understanding the size and health of their populations is a priority for both government agencies and researchers.

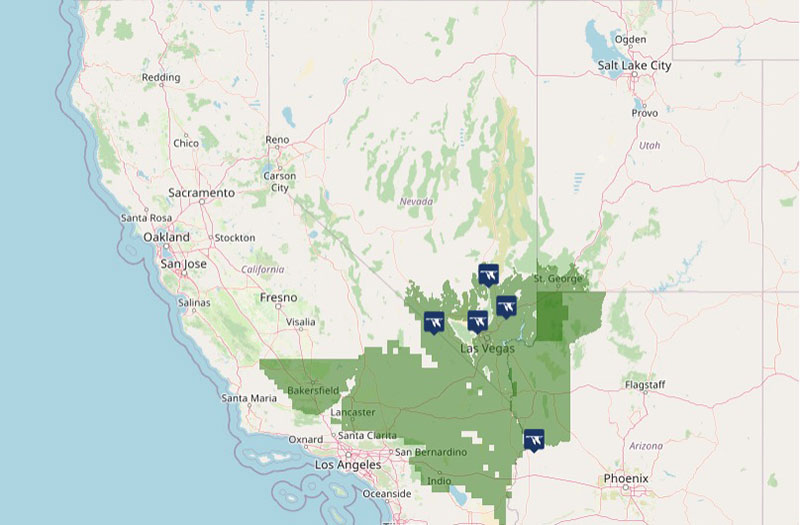

Desert tortoises occur across the Mojave and Sonoran deserts of California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona.

Credit: Map courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service.

“Desert tortoises face predation by ravens and other large birds, canids including coyotes and foxes, as well as insects such as fire ants,” said intern Amelia Porter. “They’re also victims of urbanization, military activity, mining, and alternative energy projects, which destroy their natural habitat as well as their food and water sources and deposit a multitude of pollutants.”

For their internship, Amelia Porter and Akosua Fosu worked with DRI ecologist Tiffany Pereira to survey parts of the Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument near Las Vegas for desert tortoises. Tule Springs was established in 2014 to protect the delicate desert habitat as well as rare, preserved fossils of Ice Age life – including mammoths, ground sloths, dire wolves, and American lions. The park borders northern Las Vegas and Highway 95.

“When it comes to urban-wildlife interface, Tule Springs acts as a barrier between active human development and pristine desert tortoise habitat,” said intern Akosua Fosu. “The thing is, Tule Springs National Monument is literally in people’s backyards, and it borders a major highway. The goal is to continue to use this park and enjoy all it has to offer, but to do so in a way that doesn’t disturb the desert tortoises within the monument.”

Interns Akosua Fosu and Amelia Porter locate a desert tortoise while conducting surveys.

Credit: DRI.

Searching the Desert Landscape for Clues

To help Tule Springs resource managers better understand how many desert tortoises occur across the park, as well as how they use the landscape, the research team used a method called occupancy sampling. This method combines field surveys with computer modeling to help researchers determine the proportion of habitat within an area containing evidence of a targeted species. Occupancy sampling allows scientists to determine the abundance of a species that is otherwise elusive or difficult to track.

“One way to understand where tortoises are in the park is to walk transects across the entire monument – but that’s just not feasible,” said faculty mentor Tiffany Pereira. “So, we did a different type of population sampling that could provide information on where the tortoises are. Going to the site with the interns every week has been really fun.”

The research team conducted field surveys across 20 plots, each of which they visited four times. As they walked focused lines called transects, they recorded signs of tortoise occupancy including scat, tracks, and of course, observations of live tortoises.

Intern Akosua Fosu surveys the desert landscape for signs of desert tortoise, including scat, tracks, and evidence of burrows.

Credit: DRI.

“Tortoise scat is cylindrical in shape and has lightened edges,” said Fosu. “It’s almost like a cigar – and when you break it apart, it contains plant material.”

When the researchers found a possible tortoise burrow, they looked for evidence of recent activity, like an “apron” in the dirt indicating digging, or visible tracks.

“A tortoise burrow is a half-circle shape with the top of it rounded and smooth, due to the shell eroding it over time,” Porter said. “They’re usually located in rocky areas or under vegetation.”

Desert tortoises spend much of their lives in burrows that protect them from the harsh desert sun.

Credit: Tiffany Pereira/DRI.

The students recorded any sign of desert tortoises in a survey app, including the measurements and characteristics of burrows and the presence of live tortoises or carcasses. Using the survey data, the researchers marked each plot as active or inactive for desert tortoises using a binary system. The results are analyzed using the software program PRESENCE, which provides an estimated occupancy probability of desert tortoises within an area of interest.

“Tule Springs is a newer park,” said Porter, “so they will use the data that we’ve collected over the course of the season to help determine where to place signage, or hiking trails, without disturbing desert tortoise habitat.”

One of the most important findings from their study is that many tortoises are using parts of the park that are near human activity. “That’s a big deal for management of the park,” Pereira said. “In one case, we found a tortoise less than 200 meters from a paved road. When they think about their management plans, they need to account for that.”

Joshua trees at Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument.

Credit: Matthew Dillon.

Embracing the Research Experience

For student interns Porter and Fosu, joining Pereira’s research team and spending time in the field was a truly immersive experience into the world of science.

“Being able to see some of our native flora and fauna up close was a highlight,” said Fosu. “There were days where we came across tortoises, snakes, and even jack rabbits. I also got to learn about some of our native plant species.”

Fosu, a student at Nevada State College studying biology and chemistry, entered the school year with plans to pursue a veterinary career. Her time working with Pereira reinforced her interest in working with animals, she says. “I may even consider conducting veterinary research in the future.”

Student intern Akosua Fosu finds a desert tortoise while conducting surveys.

Credit: DRI.

“Overall, I think this was a very eye-opening experience,” Fosu continued. “My goal was to gain some research experience before I graduate and I’m glad I was able to gain that through this internship. I would definitely recommend this to anyone considering a career in a STEM field.”

Intern Amelia Porter conducting a survey for desert tortoises in Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument.

Credit: DRI.

Porter, a student at the College of Southern Nevada studying environmental conservation biology, agreed that the DRI internship helped her feel more confident in her career choice. “It has not only confirmed my passion for a career in ecology and wildlife studies,” she said, “but sparked an interest in park service and in field surveying as well.”

The highlight of the semester, Porter said, was “feeling immersed in the methods of an established ecologist, and the opportunity to feel like I was a part of a project that benefitted the surrounding area.”

“I think the entire immersion program has been a fantastic opportunity,” she said, “and I hope that the program continues so it can be as inspiring to others as it has been to me.”

More Information

To learn more about the DRI Research Immersion Internship, go to https://www.dri.edu/immersion/.