In an effort to better understand urban heat islands and their impacts on our region, a group of organizations, led by the Nevada State Climate Office, is seeking volunteers to track heat on August 10 for the Reno-Sparks Heat Mapping Project. Volunteers will set out in pairs to drive or navigate a predetermined route, equipped with a GPS-equipped temperature and humidity sensor that can be affixed to a volunteer’s car. The original project date was postponed due to unusually cool weather.

Reno-Sparks Heat Mapping Project Now Recruiting Volunteers

Scientists from the Desert Research Institute (DRI) and the University of Nevada, Reno are recruiting volunteers to conduct a one-day campaign to map extreme heat across Washoe County on July 27. community volunteers will fan out across the county to collect thousands of temperature and humidity measurements from early morning through evening, taken over 3 one-hour periods.

Meet Juan Henao Castaneda

Juan Henao, Ph.D., is a new postdoc in atmospheric sciences working with John Mejia, Ph.D. Originally from Medellin, Colombia, he spent six months on DRI’s Reno campus in 2018 while working with Mejia during his doctoral studies. His primary project will be contributing to atmospheric and air quality modeling efforts, including using digital twins to investigate the effectiveness of urban heat mitigation measures.

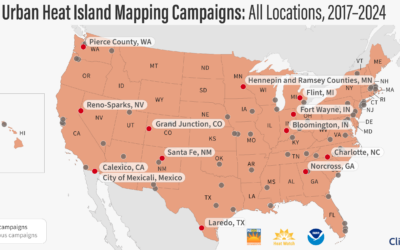

Reno/Sparks selected to be part of Urban Heat Mapping Campaign

Several municipal, county, and Tribal governments and community groups based in the Reno-Sparks area are teaming up to map the hottest parts of Reno, Sparks, and adjacent portions of Washoe County.

Meet DRI Atmospheric Modeler, John Mejia

John Mejia, Ph.D., is an associate research professor of Atmospheric Modeling at DRI. He was recently awarded a Mid-Career Advancement Award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to support his research on climate change impacts to urban communities, including urban heat islands and air pollution.

Study Launches on Extreme Heat Risk in Coastal Communities

The Desert Research Institute (DRI) and the Houston Advanced Research Center (HARC) announce the launch of a comprehensive extreme heat risk modeling project funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to study and predict the risk of extreme heat within coastal communities.

Dust Control at the Oceano Dunes

DRI researchers continue a long-term effort to help park officials understand and manage dust emissions from California’s Oceano Dunes.

Researchers identify connection between more frequent, intense heat events and deaths in Las Vegas

Photo: Hotter temperatures and longer, more frequent heat waves are linked to a rising number of deaths in the Las Vegas Valley over the last 10 years. Las Vegas, Nev. (June 4, 2019) - Over the last several decades, extreme heat events around the...

New study identifies atmospheric conditions that precede wildfires in the Southwest

Reno, Nev. (January 3, 2018): To protect communities in arid landscapes from devastating wildfires, preparation is key. New research from the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Reno may aid in the prevention of large fires by helping meteorologists and fire managers...