Meet graduate researcher Natasha Sushenko and learn about her work in DRI’s Environmental Microbiology Laboratory in this interview with DRI’s Behind the Science Blog.

Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) in the Urban Wetland Ecosystem: Las Vegas Wash

Photo: Duane Moser (left) and Xuelian Bai (right) collect filters from the sampling pump to take back to the lab for analysis. Research on antibiotic resistance genes at DRI Antibiotic resistance—the ability of bacteria to survive in the presence of antibiotics—is an...

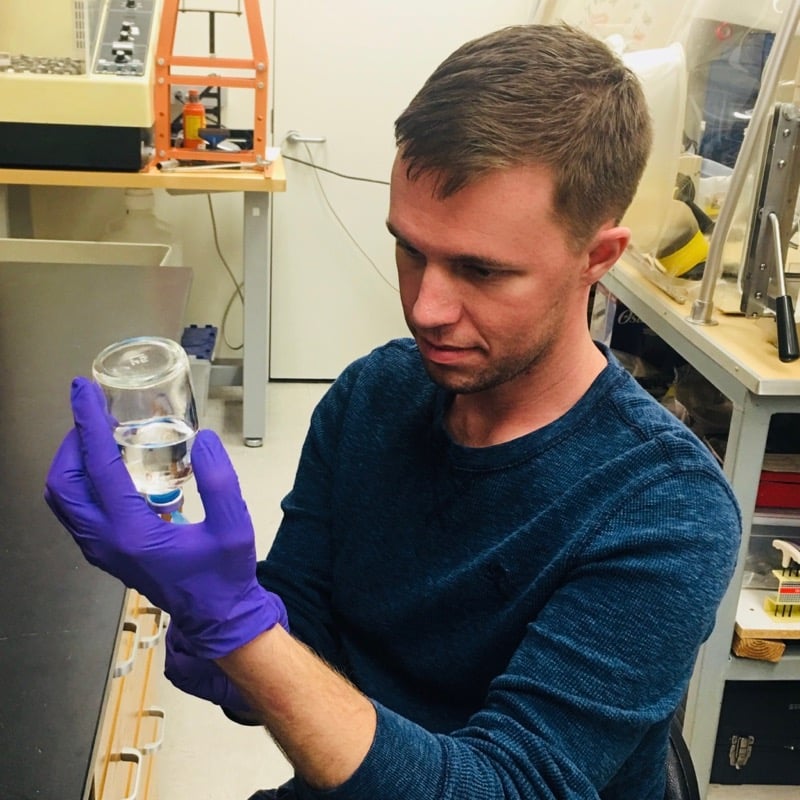

Meet Josh Sackett, Ph.D.

Josh Sackett, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral researcher with the Division of Hydrologic Sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Las Vegas.

Ancient ‘quids’ reveal genetic information, clues into migration patterns of early Great Basin inhabitants

Above: Cave opening at the Mule Springs Rockshelter in southern Nevada's Spring Mountain Range. Credit: Jeffrey Wedding, DRI. Las Vegas, NV (April 24, 2018): If you want to know about your ancestors today, you can send a little saliva to a company where – for a...

New research improves prospects for imperiled Devils Hole Pupfish in captivity

Above: Researchers Joshua Sackett (left) and Duane Moser (right) of DRI help National Park Service officials move scaffolding infrastructure during a routine sampling visit to Devils Hole on December 13, 2014. Credit: Jonathan Eisen. DRI study finds key differences...