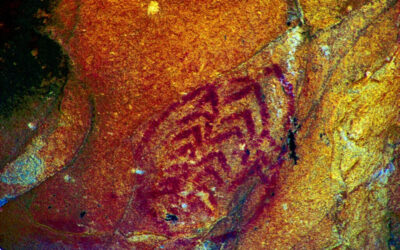

A group of Desert Research Institute (DRI) archaeologists will document ancient rock art at Fort Hunter Liggett using high resolution photography.

Preserving Nevada’s Lost City using drones

Ruins of adobe houses, Lost City of Nevada. Credit: Special Collections, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries. Nevada’s “Lost City,” located northeast of Las Vegas on a terrace above the Muddy River, has been lost twice before – first abandoned by the native people...