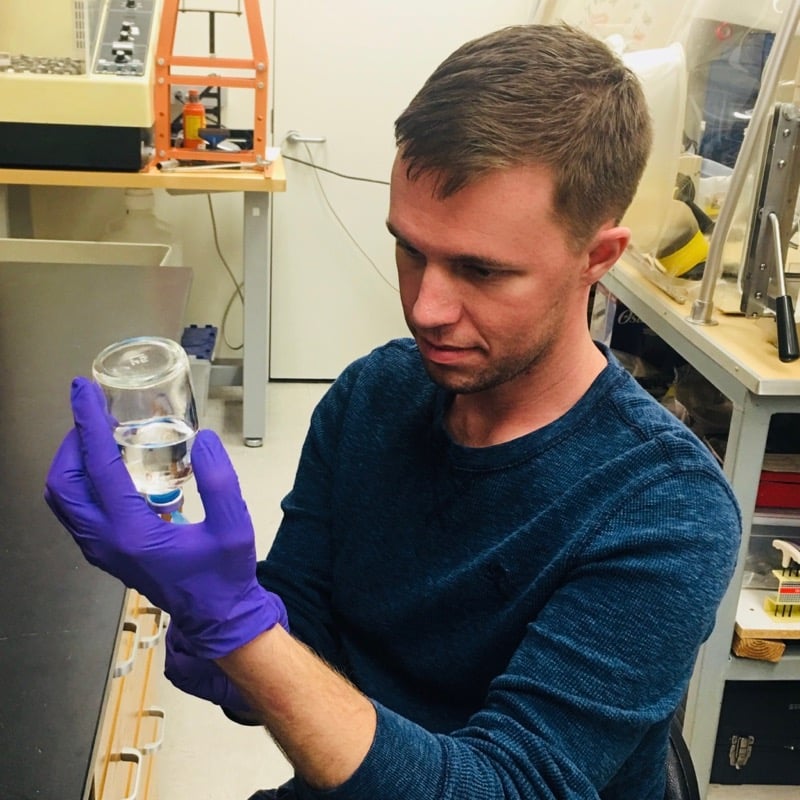

Josh Sackett, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral researcher with the Division of Hydrologic Sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Las Vegas.

New research improves prospects for imperiled Devils Hole Pupfish in captivity

Above: Researchers Joshua Sackett (left) and Duane Moser (right) of DRI help National Park Service officials move scaffolding infrastructure during a routine sampling visit to Devils Hole on December 13, 2014. Credit: Jonathan Eisen. DRI study finds key differences...