Christine Albano is an Associate Research Professor of Ecohydrology at DRI. Her research spans land, water, and air, including the implications of extreme weather, groundwater dependent ecosystems, and climate adaptation planning.

In this interview, Dr. Albano answers frequently asked questions about the relationship between a warming atmosphere and extreme weather, including wildfires, droughts, and flooding. This is the third in a new series of FAQ videos with DRI researchers.

If you’d like to see another faculty member highlighted in this series or have specific questions for our researchers, reach out to media@dri.edu.

DRI: What is the focus of your research?

Albano: My research is focused on understanding the impacts of weather variability and extremes across the Western U.S. and how it affects ecosystems, landscapes and society.

DRI: What big questions motivate your research?

Albano: I mostly grew up in the Western U.S. and dry places, and I feel like as I’ve seen water supplies become strained because of increasing population growth, I really want to focus my research on understanding how we can still thrive and sustain those water supplies amidst changing climate.

DRI: What is atmospheric thirst and what are some examples of how it’s impacting human communities?

Albano: Atmospheric thirst is essentially the amount of water that the atmosphere can pull from the land surface if it’s available. It’s a function of temperature, wind, humidity, and, that water is pulled from a land surface only if it’s available. And so, here in the West, if the water isn’t available, then it just gets hotter.

You can think of it in terms of a towel drying on a line– if you have a wet towel, under a thirsty atmosphere, it’s going to dry faster if it’s hot and windy relative to a day when it’s cooler and cloudy — the atmosphere is less thirsty under that circumstance.

So, as the atmosphere becomes thirstier as temperatures get warmer, that means less water going into our streams and reservoirs and more going up into the clouds. It means we have drier vegetation, trees might be dying. And it increases fire risk.

Some of the work that we’ve done shows there are equations you can use to quantify how much thirstier an atmosphere is as a function of temperature, wind speed, that kind of thing. And so we do have estimates of that and some of the work we’ve done looks at how that’s changed over time. In California, for example, over the past 20 years, it’s increased by 6 or 7%.

DRI: What is the relationship between atmospheric thirst and wildfires?

Albano: When the atmosphere is thirstier, it means that the vegetation is using more water and becomes drier. The soils become drier earlier in the season. And so that translates to basically a longer fire season — the time when vegetation is flammable and can carry fire if there’s a spark. And so these are definitely closely related. Again, atmospheric thirst means a longer growing season, which in turn means a longer fire season. So the probability of having a fire just increases because there’s that much more time that this could happen.

DRI: What is an atmospheric river?

Albano: Atmospheric rivers are long corridors of water vapor transport that extend from the tropics to mid-latitudes. At any given moment, there are 5 or 6 of these moving across the globe. They cover about 10% of the Earth, but carry 90% of the water vapor.

These rivers are on average the size of 28 Mississippi rivers or two and a half Amazon rivers. And when they make landfall along the coast they get uplifted by the mountains, and that water cools and condenses, and we can get large amounts of rain or snow.

DRI: In the American West, how much of our precipitation typically comes from atmospheric rivers?

Albano: That’s a good question. It depends on where you are in the West. In California, I would say 60 to 80% of our water supply comes from atmospheric rivers. As you move further inland, it’s less, because there are other weather dynamics coming into play.

DRI: How does temperature affect atmospheric thirst and atmospheric rivers? How does this impact communities?

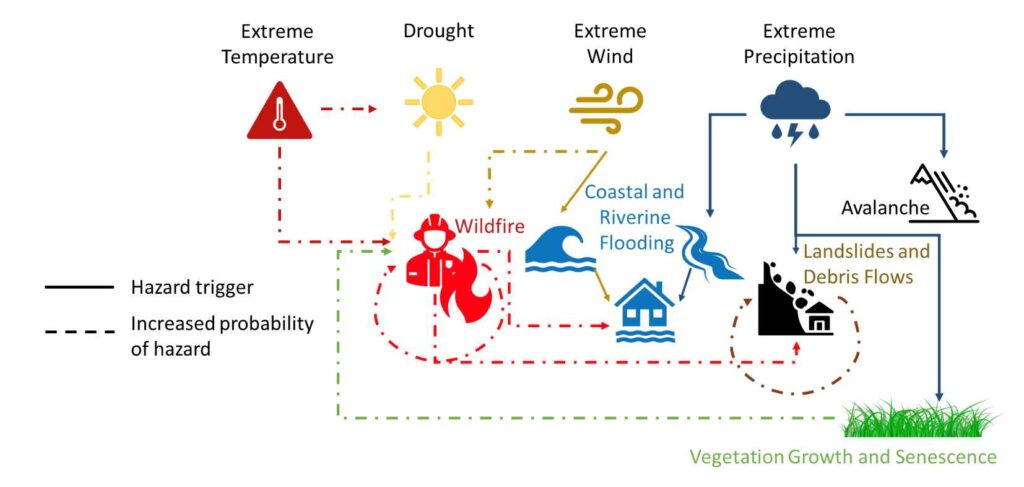

Albano: A warmer atmosphere means a thirstier atmosphere — it can hold more water. And that means drier times are drier. A thirstier atmosphere holding more water also means that our atmospheric rivers have more water. In the wintertime, that could mean that water gets released, and it’s more water than we’ve seen historically. So we can get these huge deluges of rainfall in places where historically that precipitation has been falling as snow. Because it’s warmer, we might get rain instead. So that further increases the flood risks associated with these. And so we’re seeing more wet and dry extremes that are harder to keep a balance between.

DRI: What is the impact of weather whiplash?

Albano: So one example of this weather whiplash is that in places like the Western U.S. and Southern California, and the southwest especially, we had a couple of very wet years, like 2022 and 2023, that allowed a lot of vegetation to grow. But we had a warm year this last year and that vegetation dried out and was more capable of carrying fire.

The combination of that with this wind event in January under very dry conditions where we hadn’t had much precipitation yet — these were all the ingredients that were needed for the LA wildfires.

DRI: What are some ways your research works to protect human communities?

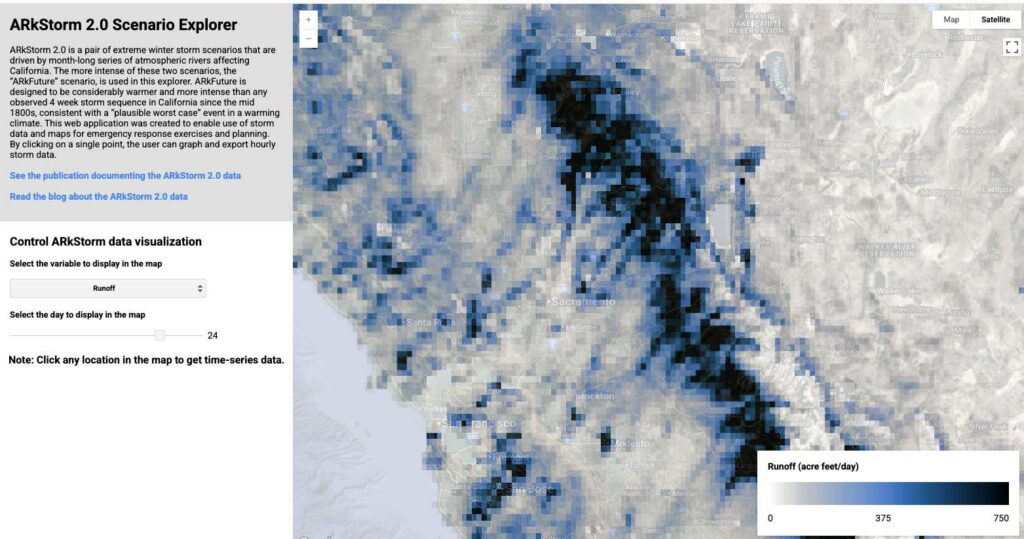

Albano: One of the ways that my research is focused on protecting human communities is through development of what we call weather extreme scenarios. So the ARkStorm scenario is one example of that, and that is a 30 day series of atmospheric river storms that are hitting the West Coast and causing extensive flooding and all sorts of other mayhem.

And so by creating something that’s scientifically plausible and realistic with a model, we have a time series of weather over this 30 day period that we can then run through hydrologic models and geologic models to look at how the impacts of that storm play out in terms of flooding, in terms of landslides or debris flows and how that affects our people and structures in cities and elsewhere.

I think the value of that is that it gives people something tangible to look at and think through. So we use these to discuss with emergency managers and community members how they would respond or prepare for these kinds of events. And again, I think this is valuable because just having a picture and a map allows them to understand more tangibly what the implications are.

When we ran the ARkStorm scenario several years ago for the Reno-Tahoe area, I’ve seen several things that water managers and emergency managers have changed as a function of going through those steps. For example, in the Lake Tahoe area, the water systems are independent of each other. And they have worked now to make sure that they can back each other up to some degree when there’s an extreme storm.

One of the greatest values of doing this work is getting people in the same room to talk about what they would do and meet each other. A lot of times we don’t even know each other, and by meeting each other, they know, oh, I can call this person, if I need X, Y, or Z. I think there’s a lot of value in that as well — it’s community building.

DRI: Could the ARkStorm Sierra Front project be a model for other communities facing potential natural disasters?

Albano: Yeah. I see ARkStorm as a model for any kind of weather extreme event, and you can use the simulations to really walk and talk through what you might do to prepare for and respond to these kinds of things.

We developed a primer for emergency managers on how to do this, including what kind of data they would need and resources. This could apply to an atmospheric river storm, it could apply to a fire, a heat wave, many other things. And so we’ve worked to develop a toolkit to help people understand how to build these kinds of things so they can have these discussions.

———

For more information about Christine Albano’s research on extreme weather, check out these stories from the DRI Newsroom:

ARkStorm Sierra Front on Youtube

Floods, Droughts, Then Fires: Hydroclimate Whiplash is Speeding up Globally

Weather Whiplash is Amplifying Wildfire Risk

DRI Scientists Create Guidance to Help Emergency Managers Prepare for Weather Hazards of the Future

New Study Offers Detailed Look at Winter Flooding in California’s Central Valley