New research examines the potential impacts of climate change on water quality in tropical reservoirs

NOVEMBER 21, 2022

LAS VEGAS, NEV.

By Elyse DeFranco

Climate Change

Water Quality

Tropical Reservoirs

Above: The Infiernillo Dam (“Little hell”), also known as Adolfo López Mateos Dam, is an embankment dam on the Balsas River near La Unión, Guerrero, Mexico. It is on the border between the states of Guerrero and Michoacán.

Credit: Arturo Peña Romano Medina, iStock Photo.

A Q&A With Study Author Erick Bandala, Ph.D.

In a new study, DRI’s Erick Bandala, assistant research professor of environmental science, worked with scientists in Mexico to address an important research gap: how will a warming climate alter water quality in tropical reservoirs? With scientists predicting that half of the world’s human population will live in tropical climates by 2050, this knowledge will be critical for adapting to a warming world.

Bandala and his coauthors developed algorithms that can be used to predict changes in water quality under the projected temperature intervals provided by climate change models developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

DRI sat down with Bandala to discuss this study and how it ties into his broader research goals.

DRI: What was the impetus for this research?

Bandala: What we’re trying to do in my lab is create technologies for climate change adaptation. Many people do research on climate change and how it will impact water availability, so there is a lot of information about how water availability will change. But something that we believe is less studied – and that is the focal point of our research – is figuring out how global warming may have an effect on water quality. This is significant because even if you have a lot of water, if the water doesn’t have the proper quality, it cannot be used, or you will need to treat it to make it usable. So, in this study, we looked at water quality parameters in a reservoir in Mexico to predict how they could change over the next 80 years or so.

But we also need to come up with solutions for how to improve the water quality so that people can use it properly without facing the risk of illness. This is what we’re trying to do in my lab. We want to come up with solutions that can help people improve the quality of their drinking water.

DRI: And what kind of solutions are you looking at?

Bandala: Well, I’m very glad that you asked that because we are developing materials that can remove contaminants from the water. And we are using the concept of circular economy, which means we want to use material that for someone is considered a waste, and turn it into something else that can be used for water treatment. For example, we have used crop waste and even plastic waste, and converted them into something that can be used to remove contaminants from water. So, we aren’t only interested in the effect of global warming on contaminants, but also in creating something that can be used for the removal of those pollutants from the water while having a low carbon and environmental footprint.

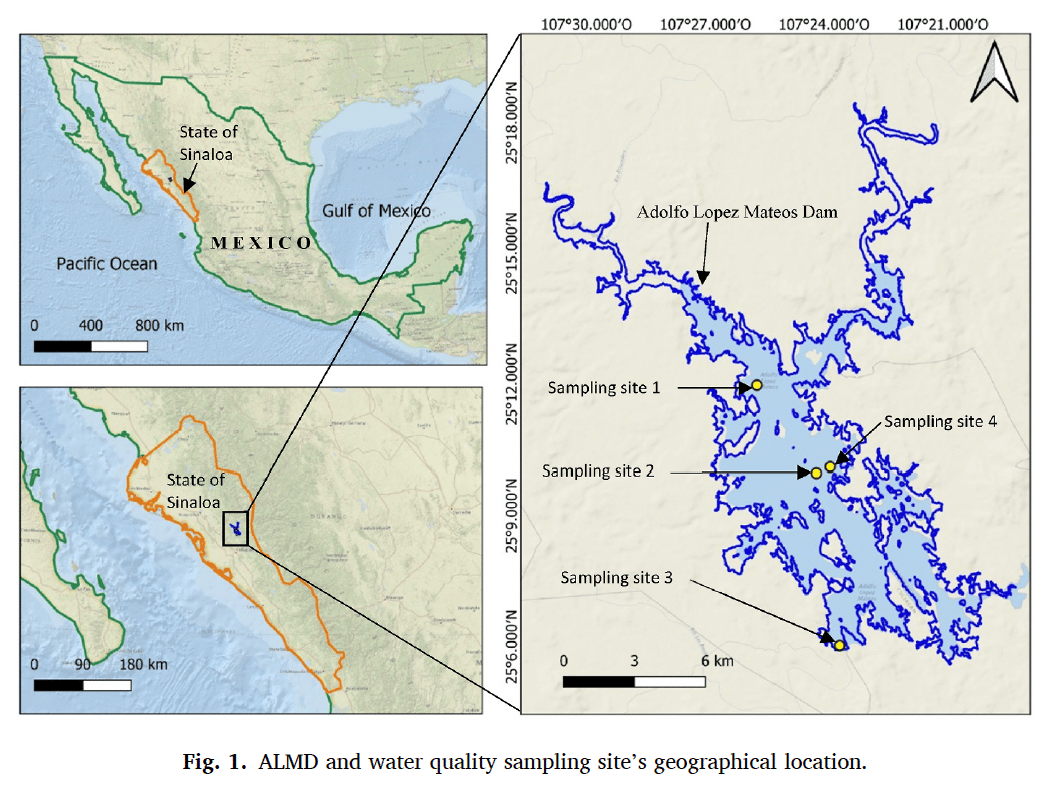

Figure 1 from the study shows the Adolfo Lopez Mateos Dam (ALMD) and water quality sampling site’s geographical location.

Credit: Erick Bandala/DRI.

DRI: That’s amazing. And how did the international collaboration with your co-authors come about?

Bandala: Well, I believe that science is not an isolated work, and less so now than ever. I think that in many cases the most help is needed in developing countries. You know in my home country of Mexico, they have a saying, “the fleas always go to the skinnier dog.” That’s very true because now many developing countries are suffering the biggest effects of climate change, and I want to help people in these countries deal with all these problems. We are developing processes, technologies, and materials that can be used for helping people in Africa, or Central America, or Asian countries that are facing huge problems with water quality.

DRI: Returning to the study, is there a reason why the study team chose to examine water quality at this particular reservoir, the Adolfo Lopez Mateos Dam in Sinaloa, Mexico?

Bandala: The main reason for choosing that site was because it had reliable water data available – it’s very complicated to get access to a good and reliable data set. Also, many of the models that have been developed in the past are for cold water bodies, and this is a warm one – the differences are significant just because of the increased water temperature in the dam.

DRI: The study showed that there was a temperature threshold where the bacteria in particular really thrived, and then above that temperature, it declined. Why is that?

Bandala: Well, bacteria are living organisms, so they have a preferred temperature range to grow in, just like everyone else. If you go too low or too high, then the reproduction or the growth of the colony will decline because it’s too hot or too cold. Now, we were very interested in microbiological contamination because this is one of the main issues in developing countries like Mexico, where many people are drinking water without the safeguards that are required. And because of that, we have very high mortality, mainly in children five years old or less. So, we wanted to understand how bacterial contamination might change under different climate scenarios.

DRI: What do you think are the biggest implications of this study?

Bandala: Well, I believe the study is probably the first one that I know of where we are really including the effects of global warming and calculating how the water quality in a water body will vary over time. In the past, I have published other papers trying to do the same, but honestly, as you said, it is highly complicated and we just partially achieved that goal. This time, I think we were really good at getting a nice model that will give us some good insight of the actual trends for a warm water body. Most of the studies are made in Canada, the U.S., or Europe, where the temperatures of the water may be in the range from 45 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. In this case we were about 70 degrees, so it’s a completely different scenario. And that makes them not only challenging, but also interesting to address.

DRI: And do you have any studies that will continue this line of work?

Bandala: Well, we’re planning to use remote sensing to corroborate the information that we created for this paper. So, if that works, it may mean that you don’t need to jump into a big data set, but can simply collect information from satellites for the analysis. Hopefully, that will be the next thing.

Erick Bandala, Ph.D., continues to work in his lab on developing materials that can remove contaminants from water.

Credit: Tommy Gugino/DRI.

Modeling the effect of climate change scenarios on water quality for tropical reservoirs

Published Sep. 5 in the Journal of Environmental Management