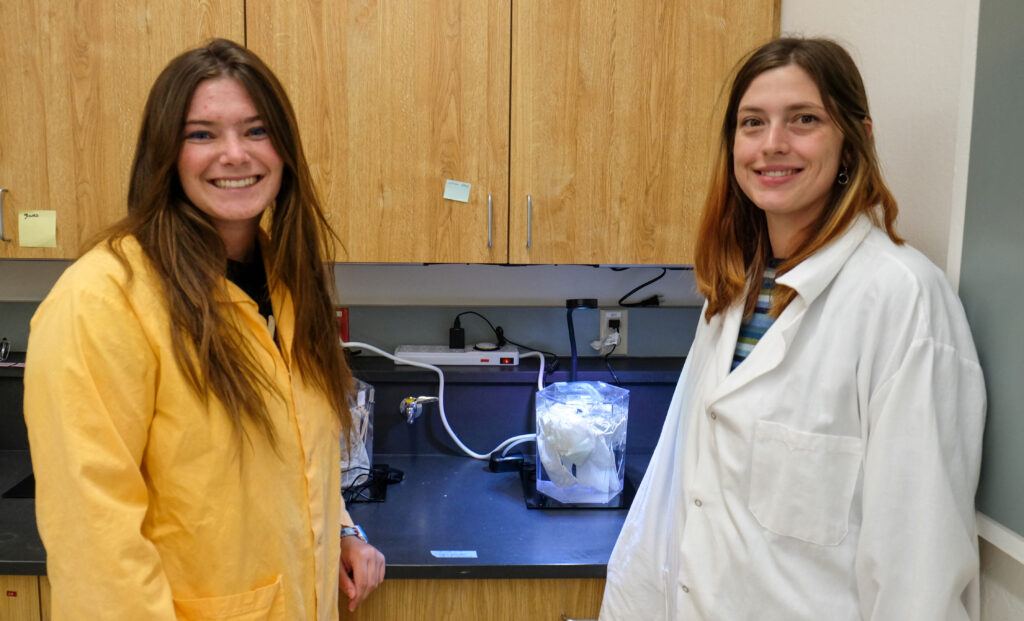

Angelique DePauw and Olivia Hines are undergraduate student researchers in the Microplastics and Environmental Chemistry Lab headed by Monica Arienzo, Ph.D. DePauw is a rising senior at the University of Nevada, Reno, studying hydrogeology, and Hines is a rising sophomore studying marine ecology at the University of San Diego. Together, they are conducting an experiment comparing the decomposition rates of plastic and plastic-alternative straws.

In the following interview, Depauw and Hines share more about what brought them to DRI, how their research experience is influencing their career trajectories, and details about their experiment.

DRI: Tell us about your background and what brought you to DRI.

DePauw: I grew up in Morro Bay, California, and actually started my college career pursuing a bachelor’s in Spanish. Due to life circumstances, I dropped out and later re-enrolled. I worked in restaurants for a long time before deciding that I wanted to pursue a job that would afford me some job longevity. And that led me to water resources, which led me to emerging contaminants, which led me to microplastics. I’ve been working as a lab technician in the microplastics lab since May 2022. One of my professors is colleagues with Monica and told me about the opening here in the lab. My career interests include emerging contaminants, and when the opportunity to join the lab came up, I was really excited. As a lab tech, I work on all kinds of projects — whatever I can help the grad students or Monica with, I’m happy to work on!

Hines: I grew up in Reno and my aunt, Yvonne Rumbaugh, is actually an employee in the Division of Hydrology — it’s fun walking by her office every day. She let me know about the summer internship. I was really excited about the opportunity because it’s kind of outside of my comfort zone — I’ve never done anything that’s not in the biological sciences. I didn’t have much knowledge about the microplastics or material science field, but I have some lab experience from school, and I’m excited to take my experience here and hopefully put it into a biological ecology lab this coming semester. I’ve been getting involved with a lot of studies here, from helping Monica out by counting snow filters from all of her microplastics in snow work, to going into the field with Rachel Kozloski. That was my very first fieldwork experience, and it was really fun and exciting.

DRI: Can you tell us about the experiment you’re running together this summer?

DePauw: The goal of our project is to investigate decomposition rates for various biodegradable straws in natural northern Nevada waters and compare this to traditional plastic straws. The idea came from the League to Save Lake Tahoe, who was approached by a company making one of these “plastic alternative” straws. The League wanted to see how their straws behave in Lake Tahoe waters.

DRI: What types of straws are you testing?

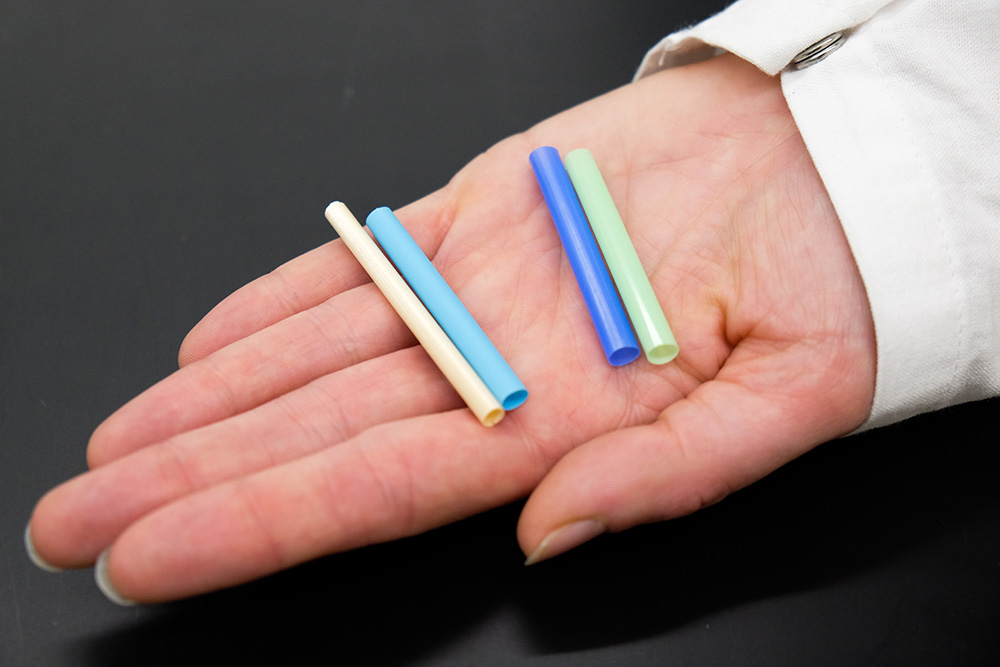

Hines: One straw we’re testing is called a PHA straw, and it’s made from canola oil and the microbes that eat canola oil under fermentation conditions. We’re also testing a classic polypropylene straw that you can buy virtually anywhere, and a “hay straw” made from wheat stems. The hay straws are interesting because they’re a byproduct of the wheat industry, because we don’t need the stems, we just need the grain.

DePauw: The fourth straw we’re testing is called PHB, which is a bioplastic similar to PHA. I really wanted to compare two different bioplastics because previous research has shown that, for example, PLA (another biodegradable plastic alternative) doesn’t necessarily degrade under natural conditions; it’s really only biodegradable in industrial composting facilities. For the sake of our experiment, we wanted to include something that hasn’t necessarily been done before. A lot of people look to bioplastics as a solution to traditional plastic, and I would like to help people decide if they’re making decisions that support their values in terms of environmentalism and sustainability.

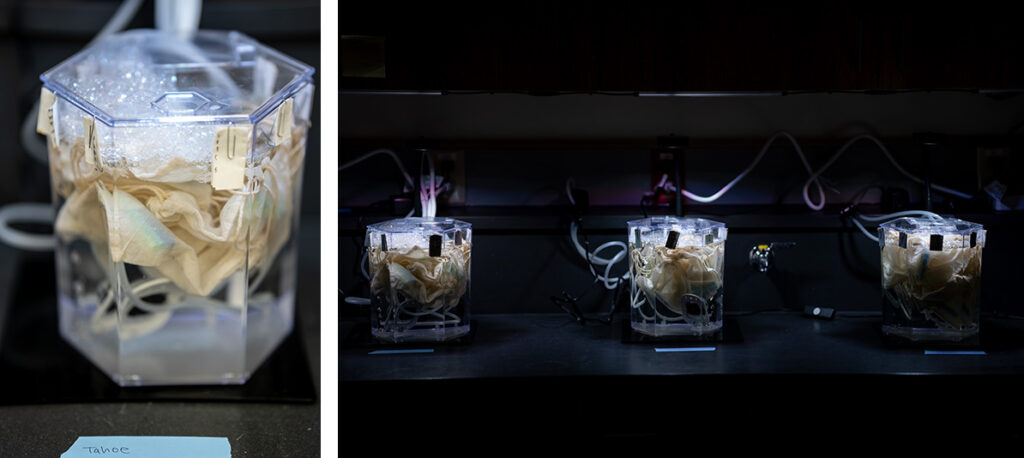

Hines: All of the bioplastic straws are similar in that the companies producing them claim they’re biodegradable in marine environments and home composting, but we couldn’t find any research on how this applies to freshwater ecosystems. So, that’s really where the need for this research came from. We’re testing Lake Tahoe water that we gathered from Tahoe City, and then we’re moving down the watershed into Truckee River water and Pyramid Lake water as well. And Sean McKenna, Ph.D. went to Bodega Bay recently, so he brought back some Bodega Bay water so we can include ocean water in our experiment.

We have tanks set up with each type of water and a small full-spectrum light, and inside are eight little cotton bags that hold each kind of straw. We’ll pull the bags out at weekly intervals to analyze the level of degradation for each type of straw over time. We made sure that each type of straw is a different color, so that in the final stages of degradation when pieces start to fall off, we’ll know which straw they belong to.

DRI: When do you expect the straws to begin breaking down?

DePauw: Most of the company-sponsored experiments claim that the bioplastics start to break down around 40 days, but these also tend to be in a marine environment. Since we’re using freshwater proxies, we expect it will take longer. We’re hoping to have results around the end of September.

Hines: They also used fairly high temperatures in their experiments, around 75 to 83 degrees Fahrenheit — which we thought was very strange. They claimed that using those temperatures would mimic a marine environment that would support a lot of life, but that doesn’t really make sense. Coastal California is one of the most productive ecosystems, and that water is significantly colder. So, we were very curious about that. And that’s part of the reason that we think they’ll take longer to break down, since we’re using ambient air temperature (about 68 degrees Fahrenheit) to eliminate introducing any more variables.

DRI: How will you measure the level of decomposition?

Hines: We’re analyzing by mass, so we have the original mass of each straw and we can dry and weigh them to look at the loss of mass. And then we’re going to use ATR-FTIR (attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared) spectroscopy, which will look at the nature of the chemicals in the straws and show the degradation of different chemicals over time. And then we’re hoping to do scanning electron microscopy which will show the surface roughness. We’ll also be able to see if any microbes appear.

DRI: What most excites you about this experiment?

DePauw: I think a lot of people are attached to convenience, and finding environmentally friendly ways to hold on to that standard that people expect is necessary within the science community. As much as you might want to change the world in broad ways, sometimes the best thing to do is focus on what’s accomplishable — and I felt like assessing straws in Nevada waters for Nevada waterways was applicable, accomplishable, and can hopefully contribute toward finding solutions.

DRI: What made you interested in studying microplastics?

DePauw: I’m interested in freshwater contaminants from a fate and transport standpoint. In many ways, the microplastics issue has been focused on the marine environment. And I view freshwater systems as one of the primary transport mechanisms for plastics and microplastics to reach marine environments. My interest was to further the understanding of how these materials move through our environment, and hopefully find solutions.

Hines: I’m studying marine ecology but am considering specializing in ornithology, and everybody has seen the really sad pictures of albatrosses opened up with big plastics in their gut. I’m wondering if maybe there are other species that aren’t ingesting as many large plastics — maybe microplastics research can be applicable to examining how migratory birds are impacted by less visible amounts of plastic contamination. I think plastics research in birds can be applied to more than just chicks that are impacted by their parents unintentionally feeding them shiny pieces of plastic.

Even though I grew up in Reno, pretty far from the sea, I’ve wanted to learn as much as I could about the ocean since I was five. I really don’t know where it came from, but my mom jokes that she was pregnant with me when she and my dad went to see Finding Nemo. It’s just been an inherent thing.

DRI: What do you like to do for fun?

Hines: When I’m in San Diego, I go to the beach and do all the San Diego stuff. I skateboard and when I have time, I cook. I’m excited to share an apartment with friends next year, because we’ll do a lot of cooking together.

DePauw: I love to cook and explore all things culinary — I spend way too much time watching Gordon Ramsay TV. And when I’m not doing that, I’m pretty outdoorsy. I like to hike, swim, and just enjoy what nature has to offer.