DRI’s Community Environmental Monitoring Program (CEMP) recently celebrated 40 years of radiation monitoring around the Nevada National Security Site, is one of the Institute’s longest-running programs – and its earliest citizen science success story.

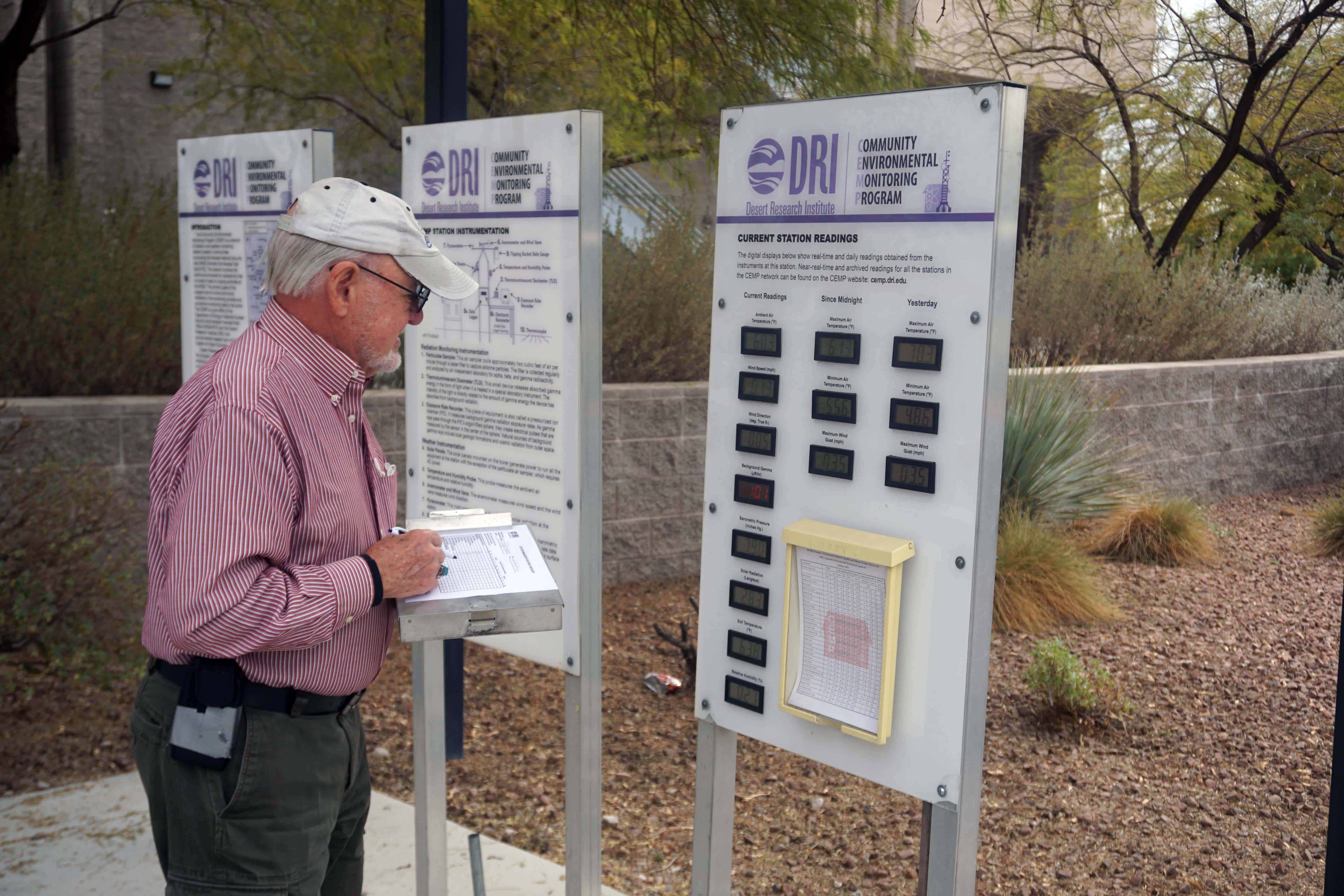

Station Manager Don Curry checks the gages at the Community Environmental Monitoring Program Station on the DRI campus in Las Vegas. Curry has been part of the CEMP since 1991.

The CEMP: a brief history

Founded in 1981 as a collaborative effort involving DRI, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Department of Energy (DOE), which funds the program through the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Nevada Field Office, the CEMP operates a network of 23 radiation and environmental monitoring stations spread throughout Southern Nevada, Utah, and California. Each station is staffed by pairs of local citizens who serve as points of contact for residents of their communities, and who are part of the official chain of custody for air filter samples they collect on a regular basis at the stations.

The program was born during a time when active nuclear testing was still going on at the NNSS. It was not long after the 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, and public distrust for the government was running high. In the aftermath of that accident, a group of local concerned citizens formed an independent monitoring network, which greatly improved public confidence in the monitoring process and results. Scientists from the DOE and EPA who had been deployed to assist with the monitoring of the Three Mile Island accident brought the idea back to Nevada, and the CEMP was born. By providing communities surrounding the NNSS with the tools to monitor radioactivity themselves and trusted community members to help interpret the data, the CEMP proved a powerful way to address citizens’ fears and concerns.

“I’m a huge proponent of giving the public a hands-on role that goes way above and beyond what the regulations might require,” said CEMP Project Director Ted Hartwell of DRI. “All of these stations are placed with the idea that we want them to be very publicly visible. A lot of them are at schools. One is at the post office in Beatty and one is at the post office in Tecopa. We have one at Southern Utah University in Cedar City and one at the BLM offices in Ely. The whole idea is that they’re visible, they’ll attract attention, and they’re staffed by trusted neighbors.”

In 1999, full technical operation of the CEMP was turned over from the EPA to DRI, and Hartwell took the helm as project director. Stations were upgraded to include meteorological instrumentation, and DRI scientist Greg McCurdy developed a program website, which for the first time allowed members of the public to access radioactivity and weather data in near real-time.

Today, DRI continues to administer the program, which employs a network of 46 Community Environmental Monitors (two per station) and 10 DRI scientists, staff members, and student interns who assist with various aspects of the program, including performing regular station maintenance, sample processing, website administration, and public outreach activities.

Troops of the Battalion Combat Team, U.S. Army 11th Airborne Division, watch a plume of radioactive smoke rise after the Dog Test at at Yucca Flats on the NNSS, Nov 1, 1951.

Station Manager Don Curry collects data at the Community Environmental Monitoring Program Station on the DRI campus in Las Vegas. Curry and a second CEMP team member visit the station three times per week.

Lessons learned

So, what has the CEMP learned over 40 years of radioactivity monitoring? For the most part, they’ve been able to show their communities that there’s nothing to be afraid of.

“This is a program that’s been around for a lot of years, but we’ve never seen anything that would be of concern to the general population,” said Don Newman, another long-time CEMP participant who began as a station manager in Cedar City, Utah in 1990.

CEMP data has helped dispel rumors and ease fears when accidents occur near the NNSS. Once, they were able to prove that a small test rocket that landed near Goldfield, Nevada was not nuclear-related. Another time, the data helped ease public concerns after an accident involving medical isotopes on the highway between Beatty and Goldfield.

The Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011 was a big moment for the program, Hartwell and Newman recall. The CEMP stations were the first to both detect and publicly report the detection of radionuclides from that accident in Japan here in Nevada.

“That was a pretty serious event, but it also really showed that our network was functioning as it should,” Hartwell said. “We were able to pick up these radionuclides of concern from a source several thousands of miles away, and yet we haven’t detected anything like that coming from the NNSS, which is just 75 or 100 miles up the road from Las Vegas, since full-scale testing ceased in 1992.

“Additionally, we were able to assist our local representatives in conveying accurate information to their communities to help them realize that, while we were certain that we were detecting radionuclides from an accident thousands of miles away, the exposure levels were thousands to millions of times less here in the United States than the ionizing radiation we’re exposed to 24/7 from the natural environment,” Hartwell added.

As time passes, public concern has shifted from the risk of airborne radiation to concern about what is in the groundwater, says Hartwell. About ten years ago, contaminants were detected in the groundwater outside the boundaries of the NNSS, but still a long way from public water sources.

The CEMP has performed water testing in the communities that are downgradient from the NNSS for decades, and works closely with Nye County, which operates a separate community-based water monitoring program, to convey the results of these studies to participants. At present, they have not detected any traces of contamination in the water, but if they do, their communities can rest assured that the CEMP monitors will be the first to let them know about it.

“It’s one of those programs where it goes along quietly for a long time, then there’s some event that CEMP participates in that really brings home the importance of the program,” said Hartwell.

More information:

For more information on the CEMP, please visit: https://cemp.dri.edu/. CEMP personnel are happy to provide presentations for classrooms, organizations or events. If you have a group interested in a presentation on the CEMP and the history of nuclear testing in Nevada, please contact Ted Hartwell (Ted.Hartwell@dri.edu) or place a presentation request through the project website: CEMP Presentation Request Form (dri.edu).

DRI faculty and staff who work on the CEMP program include: Ted Hartwell, Beverly Parker, Cheryl Collins, Greg McCurdy, Lynn Karr, John Goreham, Patriz Rivera, Pam Lacy, Rebekah Stevenson, and Sydney Wahls.