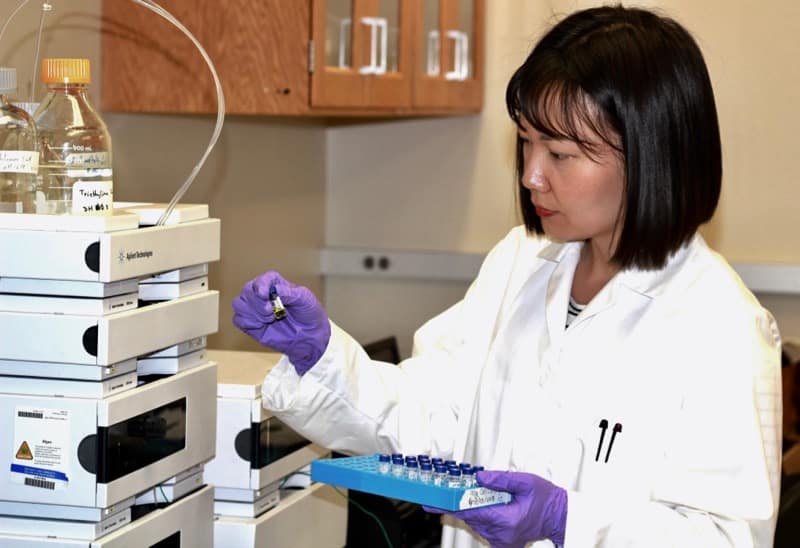

Xuelian Bai, Ph.D., Assistant Research Professor of Environmental Sciences, works with an algae sample in the Environmental Engineering Laboratory at the Desert Research Institute in Las Vegas. Credit: Sachiko Sueki. LAS VEGAS, Nev. (April 8, 2019) – A common...

Meet Erick Bandala, Ph.D.

Erick Bandala, Ph.D., is an assistant research professor of environmental science with the Division of Hydrologic Sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Las Vegas. Erick specializes in research related to water quality and water treatment, including the use of...